institute for health transformation (inhealth)

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Founder, Chief Editor and

Senior Advisor

January 25, 2023

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Background

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) survivors exhibit multisystemic alterations after hospitalization.

- Little is known about long-term imaging and pulmonary function of hospitalized patients intensive care unit (ICU) who survive COVID-19.

- We aimed to investigate long-term consequences of COVID-19 on the respiratory system of patients discharged from hospital ICU and identify risk factors associated with chest computed tomography (CT) lesion severity.

Methods

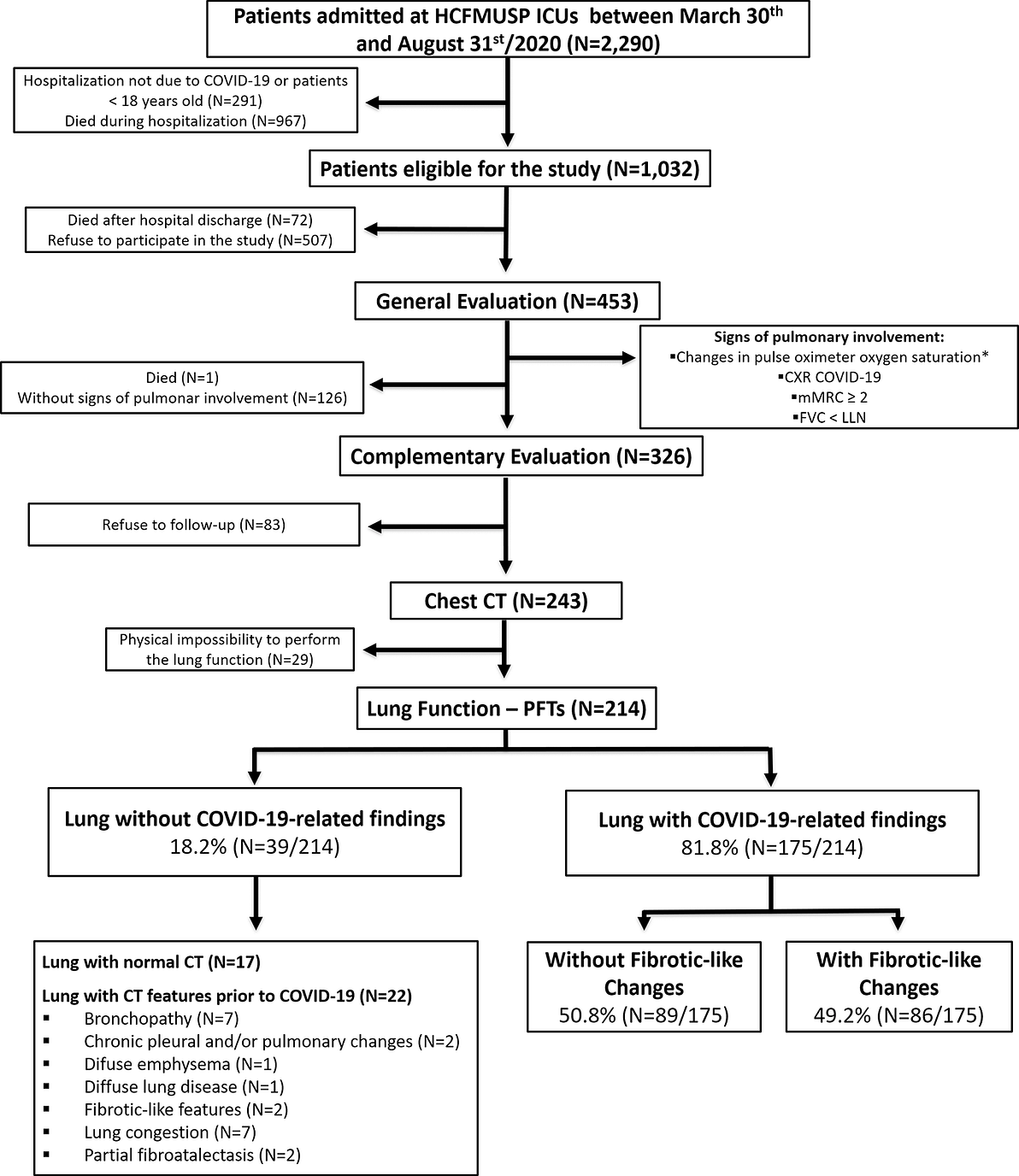

- A prospective cohort study of COVID-19 patients admitted to a tertiary hospital ICU in Brazil (March-August/2020), and followed-up six-twelve months after hospital admission.

- Initial assessment included: modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale, SpO 2 evaluation, forced vital capacity, and chest X-Ray. Patients with alterations in at least one of these examinations were eligible for CT and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) approximately 16 months after hospital admission.

- Primary outcome: CT lesion severity (fibrotic-like or non-fibrotic-like). Baseline clinical variables were used to build a machine learning model (ML) to predict the severity of CT lesion.

Results

- In total, 326 patients (72%) were eligible for CT and PFTs. COVID-19 CT lesions were identified in 81.8% of patients, and …

- …half of them showed mild restrictive lung impairment and impaired lung diffusion capacity.

- Patients with COVID-19 CT findings were stratified into two categories of lesion severity: non-fibrotic-like (50.8%-ground-glass opacities/reticulations) and fibrotic-like (49.2%-traction bronchiectasis/architectural distortion).

- No association between CT feature severity and altered lung diffusion or functional restrictive/obstructive patterns was found.

- The ML detected that male sex, ICU and invasive mechanic ventilation (IMV) period, tracheostomy and vasoactive drug need during hospitalization were predictors of CT lesion severity(sensitivity,0.78±0.02;specificity,0.79±0.01;F1-score,0.78±0.02;positive predictive rate,0.78±0.02; accuracy,0.78±0.02; and area under the curve,0.83±0.01).

Conclusion

- ICU hospitalization due to COVID-19 led to respiratory system alterations six-twelve months after hospital admission.

- Male sex and critical disease acute phase, characterized by a longer ICU and IMV period, and need for tracheostomy and vasoactive drugs, were risk factors for severe CT lesions six-twelve months after hospital admission.

Detailed conclusion

The study results show that ICU hospitalization due to COVID-19 led to chronic alterations characterized by imaging and functional abnormalities in the respiratory system that could persist for up to twelve months after hospital admission.

The high frequency of lung lesions verified was particularly concerning, mainly because severe CT lesions were more frequent in older patients with more comorbidities, who are prone to infections and acute episodes of exacerbation.

It could lead to a collapse in Brazil and the worldwide public health system, and it highlights the importance of a longer follow-up to monitor COVID-19 pulmonary consequences.

The authors believe that monitoring these patients is one way to understand the effects of COVID-19 and to create opportunities to establish public policies that would help to relieve the public health system.

The study paves the way for future investigations focusing on practical options to mitigate the consequences of long COVID-19 and highlights the necessity of longer follow-up.

INFOGRAPHIC

Fig 1. Study flow chart, showing how the COVID-19 survivors were selected to participate in this follow-up until the final numbers analyzed.

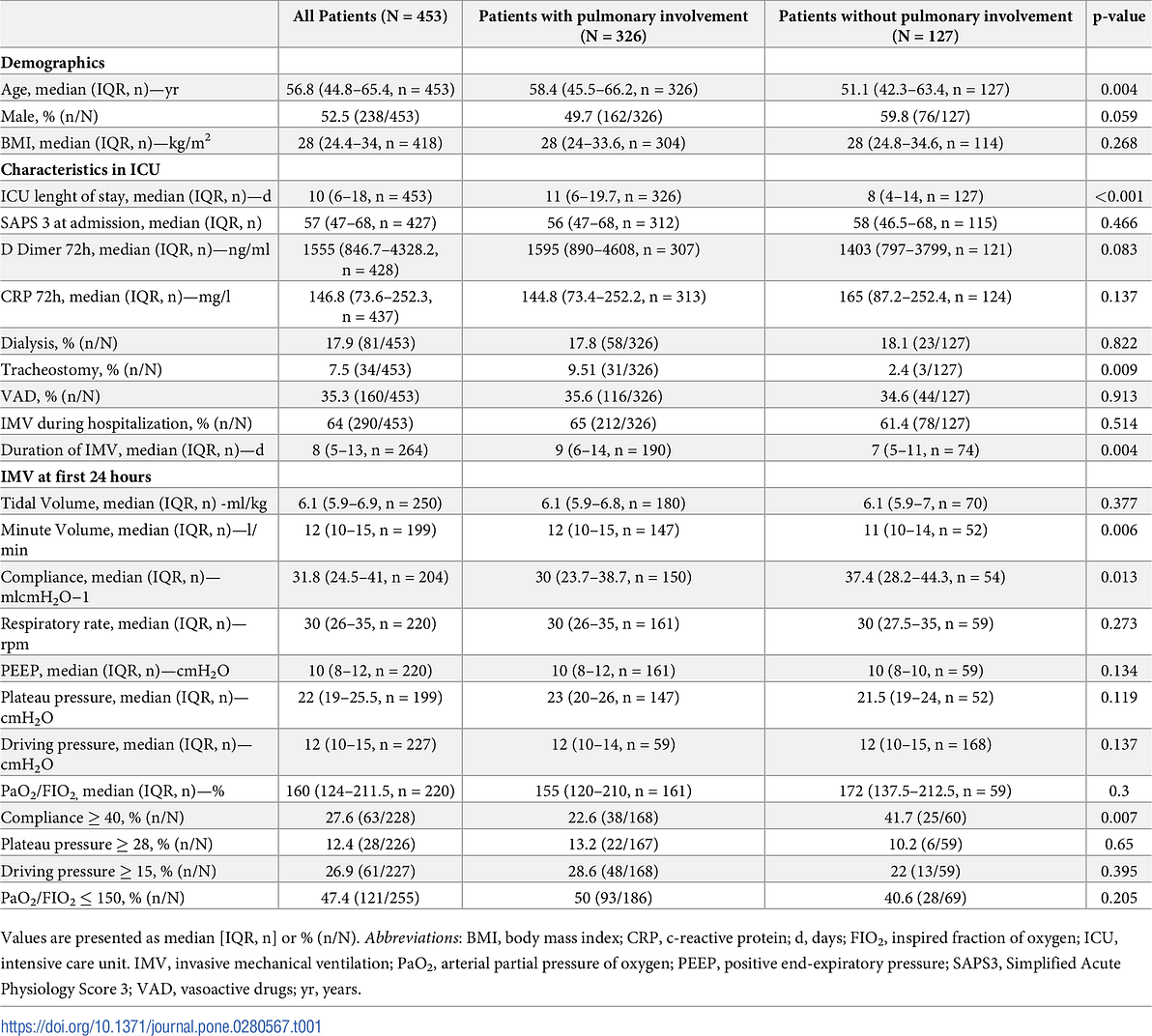

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of enrolled patients that underwent the general evaluation.

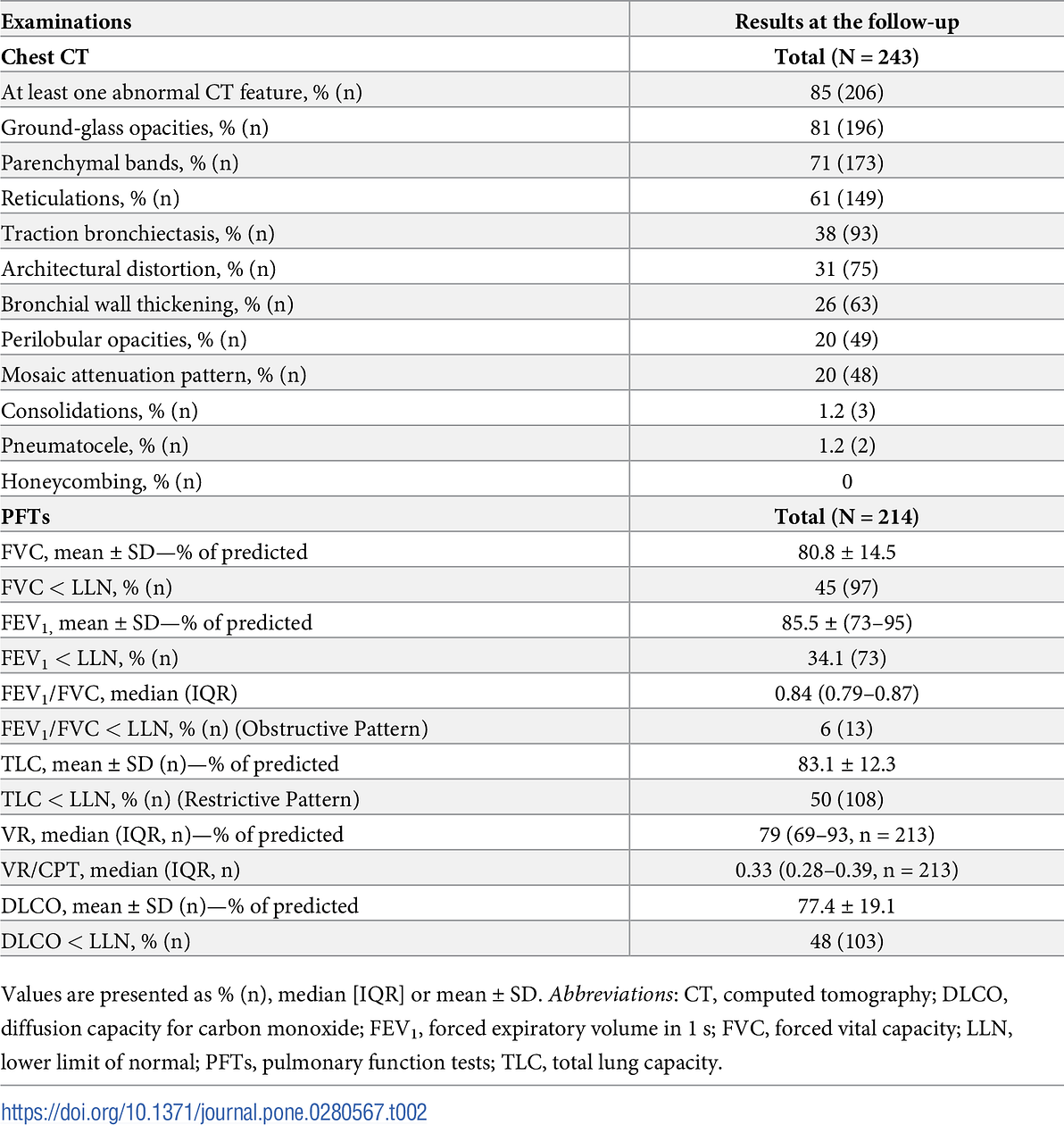

Table 2. Chest CT and PFTs among COVID-19 survivors at the follow-up.

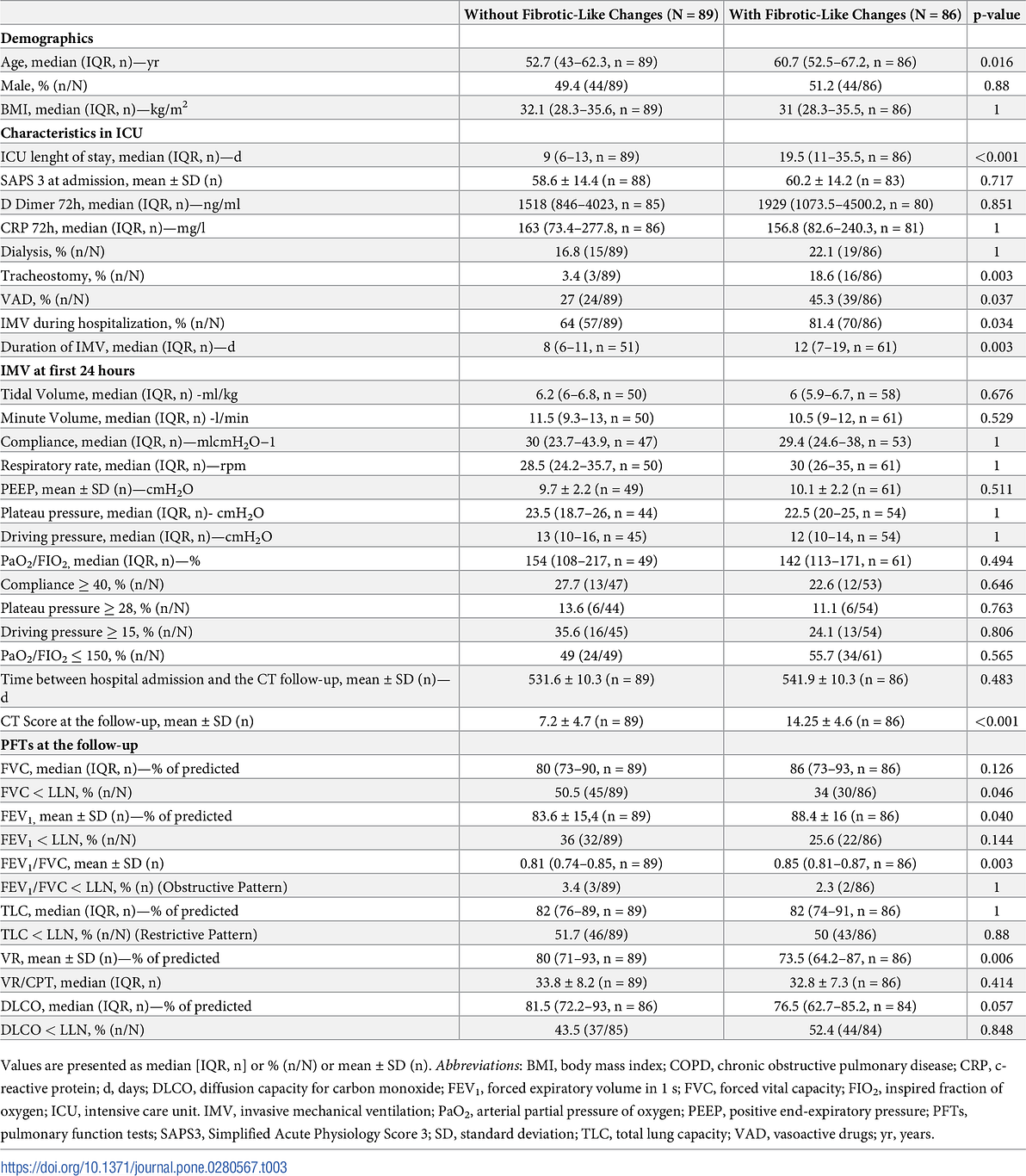

Table 3. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with completed chest CT and lung function results stratified by chest CT lesion severity.

DEEP DIVE

Long-term respiratory follow-up of ICU hospitalized COVID-19 patients: Prospective cohort study [excerpt]

Plos One

Carlos Roberto Ribeiro Carvalho ,Celina Almeida Lamas,Rodrigo Caruso Chate,João Marcos Salge,Marcio Valente Yamada Sawamura,André L. P. de Albuquerque,Carlos Toufen Junior,Daniel Mario Lima,Michelle Louvaes Garcia,Paula Gobi Scudeller,Cesar Higa Nomura,Marco Antonio Gutierrez,Bruno Guedes Baldi,HCFMUSP Covid-19 Study Group

January 20, 2023

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread worldwide since the end of 2019. SARS-CoV-2 infection triggered the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which has caused more than six million deaths globally to date [ 1].

Scientists worldwide have made efforts to clarify the clinical consequences and prognosis of the acute phase of COVID-19 [ 2– 4].

However, studies assessing the long-term consequences of this disease, especially considering the recovery of critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU), are still scarce.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has drawn attention to long COVID, which is the persistence of disease-related symptoms for more than three months after recovery [ 5– 7].

Frequent manifestations of long COVID include dyspnea, fatigue, fever, myalgia, headache, and fibrotic-like lung abnormalities [ 5, 7– 9].

A recent cohort study by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs showed that hospitalized ICU patients had a higher risk of death and pulmonary disease than non-ICU patients six months after COVID-19 infection [ 10].

Our previous study showed that 76.5% of patients who had recovered from COVID-19 still had at least one abnormality on chest computed tomography (CT) six months after hospital admission, which was more frequent in ICU than in ward patients [ 11].

Thus far, most cohort studies on recovered ICU COVID-19 patients have focused on long-term symptoms than pulmonary assessments. In view of this, a recent Dutch cohort study on 246 patients one year after COVID-19 ICU treatment demonstrated that 74% of patients still reported physical symptoms, 26% reported mental symptoms, and 16% reported cognitive symptoms.

Moreover, a larger study that evaluated 390 patients six months after recovery from COVID-19 in China was restricted to only 4% of ICU patients [ 12].

Most of those ICU patients required invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), had more comorbidities, and worse lung function, therefore, further studies are needed for a better insight.

It is well known that ICU hospitalization has inherent risk factors that could lead to future problems even in the non-COVID-19 context [ 13].

A study of survivors of other diseases caused by viruses of the SARS family showed that pulmonary sequelae can persist for up to 15 years [ 14], in addition to being correlated with a longer duration and severity of the acute phase of the disease, and consequently, the need for ICU hospitalization [ 15].

The post-recovery effects included reduced diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), restrictive pattern in pulmonary function tests (PFTs), and ground glass opacities on computed tomography (CT) scan [ 16, 17].

These previous results reinforce the well-known assumption that ICU hospitalization represents a risk factor for development of lung abnormalities in the long term and provide clues that ICU hospitalization due to COVID-19 could lead to chronic lung CT damage, which should be investigated.

Thus, it is essential to provide insights regarding ICU hospitalization that could influence the persistence of respiratory system alterations, considering that the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing and the possibility of ICU hospitalization still exists.

Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the respiratory outcomes of a consecutive large cohort of patients admitted to ICUs for COVID-19, focusing on the assessment of lung imaging and PFTs, and to determine the risk factors in the acute phase of the disease that could be predictors of chronic lung injury.

2. Materials and methods

See the original publication (this is an excerpt version)

3. Results

See the original publication (this is an excerpt version)

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest prospective cohort study of ICU hospitalized COVID-19 survivors to date that has focused on face-to-face assessment of pulmonary alterations.

The use of a protective MV protocol to treat ICU hospitalized COVID-19 patients led to increased patient survival, allowing more patients to be followed up [ 18].

Our results show that 82% of patients remain with COVID-19-related lung CT sequelae for up to twelve months of follow-up.

These long-term imaging alterations were associated with restrictive lung impairment and impaired diffusion capacity in 50% of enrolled patients.

However, even in those with fibrotic-like changes, the impairment in PFTs was mild. Additionally, male sex, ICU length of stay, duration of IMV, and need for tracheostomy and vasoactive drugs during hospitalization were predictors of CT lesion severity six to twelve months after ICU admission for COVID-19.

The general evaluation showed that COVID-19 ICU patients with initial pulmonary involvement at follow-up had low respiratory compliance, despite no significant impairment in oxygenation.

Worse respiratory mechanics in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) non-COVID were previously associated with impaired production of pulmonary collagen and independently associated with tomographic and physiological abnormalities after ARDS [ 25].

This suggests that the reduction in respiratory mechanics, in addition to indicating greater severity of acute lung injury, may increase the risk of pulmonary impairment, perhaps due to the high difficulty associated with adjusting protective ventilatory parameters in these patients.

However, this difference was slight, and this hypothesis should be confirmed in future studies.

We found that half of the patients with lung CT with COVID-19 abnormalities had restrictive lung impairment and impaired diffusion capacity. Bellan et al. [ 26] evaluated a cohort of 200 patients one year after COVID-19 discharge.

Their results showed that a high chest CT severity score is one of the most relevant factors associated with low DLCO, as this functional impairment may be secondary to the extent of the pulmonary parenchymal lesions.

Additionally, these authors showed that the percentage of patients with impaired DLCO showed no functional improvement from 4 to 12 months of follow-up after COVID-19 hospital discharge, which reinforces the hypothesis of chronic functional impairment.

Follow-up studies have demonstrated that lower DLCO is more frequent than lower TLC in survivors of COVID or ARDS [ 12, 17, 26– 28].

Hui et al. [ 28] evaluated the PFT outcomes of patients 1 year after hospitalization for ARDS showing a post-discharge frequency of 24% of patients with impaired DLCO and only 5% of patients with low TLC.

Notably, they also observed that all PFT predicted values (%) were lower in ICU patients than in ward patients.

The incidence of restrictive patterns was higher in our study, which could be a consequence of the critical acute phase of the disease in our population, considering that the other studies evaluated a mixed population of non-ICU and few ICU patients.

A recent meta-analysis of parenchymal lung abnormalities following hospitalization for COVID-19 assessed follow-up studies within twelve months and showed that fibrotic sequelae were estimated in 29% of patients, which is consistent with our findings [ 29].

Ground-glass opacities and reticulation were considered non-fibrotic lesions because of the belief that resolution during follow-up was possible, whereas traction bronchiectasis and/or architectural distortion were classified as fibrotic-like changes since they are typically considered more definitive changes [ 20, 26].

Our findings demonstrated that CT lesion severity did not point to a higher functional limitation, since all CT patterns were associated with mild functional impairment.

Fortini et al. [ 30] evaluated a cohort of patients one year after COVID-19 discharge and, showed that functional improvement was not associated with complete tomographic resolution.

In addition, Han et al. [ 31] did not observe differences in PFTs in a cohort of Chinese patients stratified by the presence or absence of fibrotic interstitial lung abnormalities at the one year COVID-19 follow-up.

These results indicate that structural recovery may be slower than functional improvement after COVID-19.

Therefore, anatomical sequelae seem to have little functional repercussions, indicating that respiratory evaluation after COVID-19 infection should focus more on functional and clinical evaluation rather than imaging.

Our study also revealed that patients with fibrotic-like changes had a more severe acute phase characterized by longer hospital stay and greater need for IMV and tracheostomy than patients without fibrotic-like changes up to twelve months after COVID-19 hospitalization.

Thus, we used an ML to identify the predictors of CT lesion severity at follow-up.

Our results showed that male sex, ICU length of stay, duration of IMV, need of tracheostomy, and use of vasoactive drugs are risk factors for CT lesion severity six to twelve months after COVID-19 ICU admission.

Previous data reinforce our findings, demonstrating that male sex [ 32] and length of hospital stay [ 33] were associated with severe CT lesions one year after COVID-19 hospitalization.

Invasive respiratory procedures, such as IMV and tracheostomy, have the inherent potential to induce structural and functional damages to the lung due to inadequate pressure or volume [ 34].

Additionally, both IMV and vasoactive drugs administered during ICU hospitalization have been associated with increased mortality and complications after discharge [ 35].

Other characteristics and factors identified during the acute phase of COVID-19 that are associated with a higher risk of development of fibrotic pulmonary lesions in the follow-up of COVID-19 patients in previous studies include a higher CT score of lung involvement, use of high-flow oxygen support, duration of mechanical ventilation, obesity, male sex, smoking, diabetes, and higher levels of C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase, D-dimer, and fibrinogen [ 8, 20, 32, 36, 37].

Additionally, persistent dyspnea and myalgia and higher serum levels of Krebs von den Lungen 6 (KL-6) at follow-up were associated with a greater risk of occurrence of post-COVID pulmonary fibrosis [ 31, 37, 38].

Our study had several limitations.

First, plethysmography was not performed in all patients who underwent chest CT, reducing (12%) the number of patients evaluated by both methods. Such an examination was not feasible in some cases due to patient limitations (tracheostomy, wheelchair use or intellectual difficulties).

Second, we did not exclude patients with COPD. Nevertheless, the number of these patients was small (7%) and, data accuracy was not affected.

Another limitation was the recruitment period: we enrolled patients six to twelve months after hospital admission. This recruitment period was selected because it occurred during the first wave of the pandemic when there were restrictions to control the virus, and fear drove people away from hospitals. However, the median follow-up time was approximately 7 months, and most patients enrolled were followed up on time without impacting data accuracy.

In addition, the study design allowed mainly the most affected patients to reach the stage of performing chest CT. Thus, patients “without COVID-19-related lesion” included patients with normal chest CT and patients with pre-existing lesions unrelated to COVID-19. This fact contributed to these patients having a lower FVC and FEV1 than patients with COVID-19 lesions, not representing an ideal control group (without lesions) for comparison purposes.

In addition, there is variability in the definition of long COVID fibrotic-like changes in the scientific literature. Although previous data have included reticular opacities as indicative of fibrosis, we understand that, at least in some patients, they may be relatively mild and only associated with ground-glass opacities, which could represent an inflammatory process in resolution, especially organizing pneumonia.

Therefore, to increase the specificity of tomography as a method of detecting long COVID definitive fibrosis, our group decided to consider well-established imaging findings indicative of fibrosis (not only in long COVID scenarios, but also in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias), including traction bronchiectasis, architectural distortion, and honeycombing (which was not found in our cohort).

Finally, this was a single-center study. However, HCFMUSP is the largest university hospital in our country and, has been designated as a reference hospital to treat COVID-19 patients.

Thus, during the COVID-19 pandemic, heterogeneous groups of people of different ethnicities from all districts of the metropolitan region of São Paulo city (approximately 21 million inhabitants) were admitted to this hospital [ 18].

5. Conclusion

Our results show that ICU hospitalization due to COVID-19 led to chronic alterations characterized by imaging and functional abnormalities in the respiratory system that could persist for up to twelve months after hospital admission.

The high frequency of lung lesions verified was particularly concerning, mainly because severe CT lesions were more frequent in older patients with more comorbidities, who are prone to infections and acute episodes of exacerbation.

It could lead to a collapse in Brazil and the worldwide public health system, and it highlights the importance of a longer follow-up to monitor COVID-19 pulmonary consequences.

We believe that monitoring these patients is one way to understand the effects of COVID-19 and to create opportunities to establish public policies that would help to relieve the public health system.

Our study paves the way for future investigations focusing on practical options to mitigate the consequences of long COVID-19 and highlights the necessity of longer follow-up.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the infrastructure support from the HCFMUSP COVID-19 task force (Antonio José Pereira, Elizabeth de Faria, Lucila Pedroso and Marcelo CA Ramos) during the baseline stage of in-hospital data collection and during the setting-up of the follow-up assessments.

*Members of the HCFMUSP Covid-19 Study Group: Adriana L Araújo 1, Aluisio C Segurado 2, Amanda C Montal 3, Anna Miethke-Morais 3, Anna S Levin 4, Beatriz Perondi 3, Bruno F Guedes 5, Carolina Carmo 3, Carolina S Lázari 6, Cassiano C Antonio 7, Clarice Tanaka 8, Claudia C Leite 9, Cristiano Gomes 10, Edivaldo M Utiyama 11, Emmanuel A Burdmann 12, Eloisa Bonfá 3, Esper G Kallas 2, Ester Sabino 13, Euripedes C Miguel 14, Fabio R Pinna 15, Geraldo F Busatto 14, Giovanni G Cerri 16, Heraldo P Souza 17, Izabel Marcilio 18, Izabel C Rios 3, Jorge Hallak 10, José Eduardo Krieger 19, Juliana C Ferreira 7, Julio F M Marchini 20, Larissa S Oliveira 7, Leila Harima 21, Linamara R Batisttella 22, Luis Yu 5, Luiz Henrique M Castro 5, Marcelo C Rocha 23, Marcello M C Magri 24, Marcio Mancini 25, Maria Amélia de Jesus 3, Maria Cassia J M Corrêa 2, Maria Cristina P B Francisco 3, Maria Elizabeth Rossi 3, Marjorie F Silva 3, Marta Imamura 25, Maura S Oliveira 24, Nelson Gouveia 3, Orestes V Forlenza 14, Paulo A Lotufo 6, Ricardo F Bento 27, Ricardo Nitrini 5, Rodolfo F Damiano 14, Roger Chammas 28, Rossana P Francisco 29, Solange R G Fusco 30, Tarcisio E P Barros-Filho 3, Thais Mauad 31, Thaís Guimarães 3, Thiago Avelino-Silva 3, Vilson C Junior 3and Wilson J Filho. Affiliations: 1 Diretoria Executiva dos LIMs, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo HCFMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 2 Divisao/Departamento de Molestias Infecciosas e Parasitarias, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, SP, BR. 3 Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, SP, BR. 4 Departamento de Moléstias Infecciosas e Parasitárias do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. 5 Departamento de Neurologia, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo HCFMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 6 Divisão de Laboratório Central do Hospital das Clínicas, da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. 7 Pulmonary Division, Heart Institute (InCor), Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo (HCFMUSP), Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil. 8 Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina, University of São Paulo, Brazil; Department of Physiotherapy, Communication Science and Disorders, Occupational Therapy, University of São Paulo, Brazil. 9 Radiology Institute (InRad), Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo (HCFMUSP), Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil. 10 Division of Urology, Hospital das Clinicas, University of Sao Paulo Medical School, Sao Paulo, Brazil. 11 Division of General Surgery and Trauma, Department of Surgery, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (HC/FMUSP), São Paulo, Brazil. 12 Laboratório de Investigação (LIM) 12, Serviço de Nefrologia, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. 13 Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo, Laboratório de Investigação Médica (LIM 46), São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. 14 Departamento e Instituto de Psiquiatria, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo HCFMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 15 Division of Otorhinolaryngology, University of São Paulo, Brazil. 16 Departamento de Radiologia, Faculdade de Medicina, LIM/44, Laboratório de Ressonância Magnética em Neurorradiologia Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 17 Departamento de Clínica Médica, Disciplina de Emergências Clínicas, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo HCFMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 18 Epidemiological Surveillance Department, Hospital das Clinicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil. 19 Laboratório de Genética e Cardiologia Molecular, Instituto do Coração (InCor), Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo (HCFMUSP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 20 Emergency Department, Hospital das Clı´nicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. 21 Clinical Director’s Office, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. 22 Departamento de Medicina Legal, Etica Medica e Medicina Social e do Trabalho, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo HCFMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 23 Divisao de Clinica Cirurgica III, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, SP, BR. 24 Division of Infectious Diseases, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. 25 Instituto de Medicina Física e de Reabilitação, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil. 25 Unidade de Obesidade e Síndrome Metabólica, Disciplina de Endocrinologia e Metabologia, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo HCFMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 26 Centro de Pesquisa Clínica e Epidemiológica, Hospital Universitário, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. 27 Divisão de Otorrinolaringologia, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo HCFMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 28 Centro de Investigação Translacional em Oncologia, Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. 29 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Sao Paulo Medical School, Sao Paulo, Brazil. 30 Rheumatology Division, Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil. 31 Departamento de Patologia, LIM/05- Laboratório de Poluição Atmosférica Experimental, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo HCFMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 32 Division of Geriatrics, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, Brazil. Lead author email contact: geraldo.busatto@hc.fm.usp.br.

References & additional information

See the original publication

Originally published at https://journals.plos.org.

Citation:

Ribeiro Carvalho CR, Lamas CA, Chate RC, Salge JM, Sawamura MVY, de Albuquerque ALP, et al. (2023) Long-term respiratory follow-up of ICU hospitalized COVID-19 patients: Prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 18(1): e0280567. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280567

Editor: Yu Ru Kou, Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, TAIWAN

About the authors & affiliations

Carlos Roberto Ribeiro Carvalho ID1 *, Celina Almeida Lamas 1 , Rodrigo Caruso Chate 2 , João Marcos Salge 1 , Marcio Valente Yamada Sawamura 2 , Andre´ L. P. de Albuquerque 1 , Carlos Toufen Junior 1 , Daniel Mario LimaID 3 , Michelle Louvaes Garcia 1 , Paula Gobi Scudeller 1 , Cesar Higa Nomura 2 , Marco Antonio Gutierrez 3 , Bruno Guedes Baldi

ID 1 , HCFMUSP Covid-19 Study Group

1 Pulmonary Division, Heart Institute (InCor), Hospital das Clınicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo (HCFMUSP), Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil,

2 Radiology Institute (InRad), Hospital das Clı´nicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo (HCFMUSP), Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil,

3 Informatics Division, Heart Institute (InCor), Hospital das Clınicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo (HCFMUSP), Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil