One year on: vaccination successes and failures

The Economist (EIU)

November 11, 2021

Q4 Global Forecast

December will mark the first anniversary of the launch of the global vaccination campaign against coronavirus (Covid-19).

Raw data paint a picture of success: as at late October, more than 7bn shots have been administered around the world.

However, regional- and country-level figures shed a different light on the story:

· some (mostly developed) countries have succeeded in vaccinating large percentages of their populations,

· but many (mostly developing) countries have made only negligible progress.

As well as publishing the latest EIU global map of vaccination timelines, this white paper presents some vaccination success and failure stories and discusses their political and economic implications.

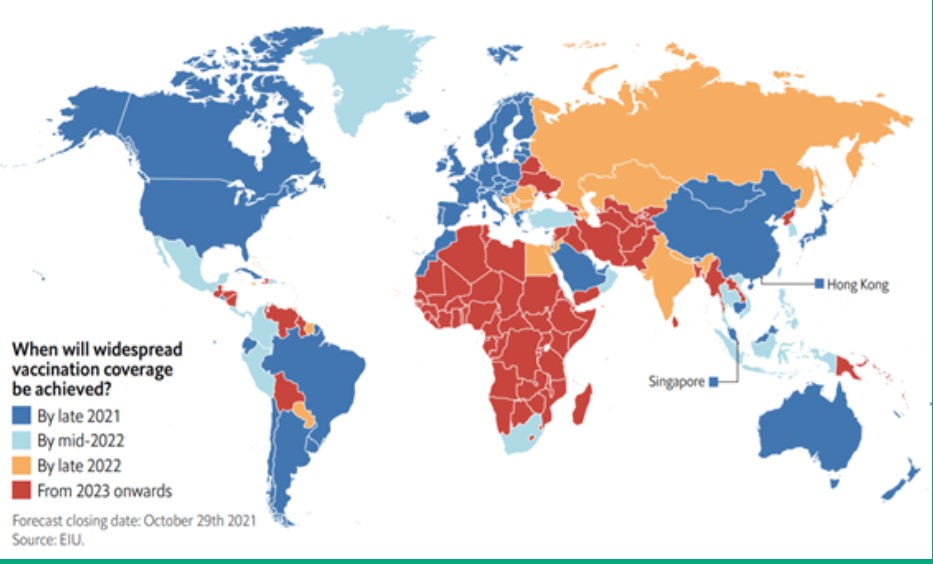

Rich countries will have vaccinated the bulk of their populations earlier than others

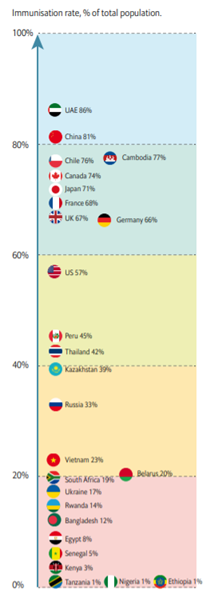

Vaccination coverage against Covid-19 varies greatly across countries

To October 29th 2021. Vaccination is defined as a full course of immunisation, usually with two shots. Sources: Government websites; EIU.

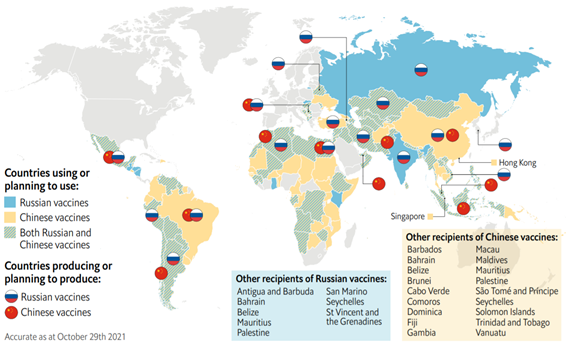

China’s and Russia’s vaccine diplomacy spans the globe

Sources: WHO; UNICEF; government websites; company websites; press reports; EIU.

Selected Case studies

- Canada

- Russia

- Chile

- Cambodia

- Africa

Canada: the hare, the tortoise and the federal election

Canada’s vaccination story is that of a slow start, followed by one of the fastest inoculation campaigns in the world. This success was not a given; in early 2021, when most other G7 economies had already vaccinated the majority of their vulnerable citizens, Canada was lagging far behind — posting a vaccination rate of only 1%. This looked like a paradox: Canada had pre-booked the highest number of vaccines per capita (at around ten doses per resident). Nevertheless, the issue lay elsewhere, in Europe. Concerned that the US would not export coronavirus vaccines even to its neighbours, the Canadian government had decided to procure vaccines solely from European plants. However, production delays were rife in Europe at the time; the world was discovering that manufacturing vaccines was far from straightforward and that vaccine factories could take weeks to get up to full capacity.

This situation put the government of prime minister Justin Trudeau under tremendous pressure. Against all odds, Mr Trudeau’s administration maintained his forecast that all Canadians would be able to receive a vaccine by the end of the summer. History proved Mr Trudeau right. From March, European production problems began to subside, and Canada began a rapid roll-out that relied on the country’s well-developed provincial vaccination infrastructure. By early August, more than 60% of Canadian residents had been fully vaccinated, one of the highest rates in the world at that time. This positive outcome undoubtedly contributed to Mr Trudeau’s re-election in September, highlighting how vaccination programmes have become political assets — or liabilities — for governments.

Russia: vaccine hesitancy kills

On paper, Russia was all set for a fast roll-out of coronavirus vaccines; the country was the first in the world to register a vaccine (Sputnik V), building on decades of expertise in the field.

In addition, the Russian government, as part of its “vaccine diplomacy” initiative, made a huge effort early on to promote Sputnik V as a reliable alternative to Western-made vaccines.

However, almost a year on, Russia’s domestic and global vaccination drives have failed: as at late October, only one-third of Russian residents were vaccinated, and many of the countries that planned to use Sputnik V are looking at alternatives.

Russia’s vaccination failure is due to two factors.

- The first is vaccine hesitancy, which is very high across former Soviet countries; only 40–45% of Russians are willing to receive a vaccine against coronavirus, a proportion that has not budged in recent months, despite a spike in coronavirus cases and deaths.

Even vaccine mandates have proved ineffective in a country where a significant share of the population believes coronavirus vaccines to be “experimental”. Instead, mandates have encouraged the development of an industry dispensing fake vaccination certificates. - The second problem is manufacturing issues, which have plagued the production of second doses of Sputnik V and undermined Russia’s vaccine-diplomacy efforts. Russia’s failure to vaccinate its population has had dire consequences.

According to data from The Economist, our sister newspaper, the country has the fifth-highest death toll per capita in the world (after Peru, Bulgaria, Serbia and North Macedonia), with an estimated 800,000 excess deaths since early 2020.

This tragedy will weigh on the country’s economic outlook for many years, especially as Russia’s demographic prospects were bleak even before the pandemic started.

Chile: a cautionary tale of fast vaccination gone wrong

Chile’s roll-out of coronavirus vaccines started early and proceeded swiftly. By May, 42% of Chilean residents had been vaccinated, far ahead of most developed countries at the time.

Six months later, Chile posts one of the highest vaccination rates worldwide, at 79%. Beyond Chile’s universal healthcare system and robust vaccination infrastructure, as well as its significant effort to secure vaccines early, the rapid roll-out of jabs is also a result of China’s vaccine-diplomacy efforts. Chile secured huge supplies of the Chinese-made Sinovac jab early on and received a first batch in late January, boosting a vaccination campaign that had been sluggish up to that point.

By May, Sinovac had become the vaccine of choice in Chile and was used for 90% of shots. Chile is not an isolated case; many other Latin American countries, including El Salvador, Mexico and Uruguay, are also relying on Chinese vaccines.

However, this fast roll-out did not prevent things going wrong for several months. High vaccination rates made the Chilean authorities overconfident that the worst of the pandemic was over.

They relaxed coronavirus-related restrictions from May, at a time when fewer than half of the population was vaccinated — with a Sinovac shot that has proved to be less effective than other vaccines against the Delta variant, which was fast becoming dominant globally. A consequent upsurge in cases forced Chile back into a lockdown, which gradually helped to bring case and death rates down from August.

The Chilean government is now trying to diversify its portfolio of vaccines, with additional orders of Pfizer, Moderna and Sputnik V shots.

In parallel, the country has also launched a booster programme, this time using the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines. However, receiving deliveries of non-Chinese vaccines will not be easy at a time when global supply is failing to meet huge demand.

Cambodia: China’s vaccine diplomacy in full swing

Judging by countries at similar levels of development, Cambodia was set to vaccinate the majority of its population by late 2022 or early 2023. Yet, by October, the country had achieved one of the highest inoculation rates worldwide, with nearly 80% of Cambodian residents vaccinated (ahead of all other Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, except Singapore). This success is down to three factors. First, Cambodia secured supplies of Chinese-made vaccines early on as part of China’s vaccine-diplomacy drive to sell jabs to emerging countries. In doing so, Cambodia made what proved to be a prescient prediction: that the World Health Organisation (WHO)-sponsored COVAX mechanism would not turn out to be a reliable way for developing countries to access vaccines. Second, the Cambodian government enlisted the help of the military to address shortages of healthcare workers, especially in rural areas. This, too, proved a successful tactic: in many other Asian countries, including India and Bangladesh, the lack of healthcare personnel is impeding vaccination drives. Third, the Cambodian authorities were careful not to lift social-distancing restrictions before they reached high levels of immunisation coverage.

Cambodia’s speedy vaccination roll-out means that the country’s short-term economic prospects are brighter than those of its neighbours, such as Thailand and Vietnam. This will be especially true in the tourism sector, which represents around 12% of the Cambodian economy. The Cambodian government plans to re-open borders by end-2021 through a “Cambodia safe” campaign that seeks to reassure tourists who are concerned about safety. Yet, despite these efforts, tourist numbers are unlikely to return to pre-pandemic levels for several years; we expect China, the main country of origin for tourists visiting Cambodia, to maintain strict controls and quarantines for returning travellers in 2022.

Africa: still no shots in sight

Africa’s vaccination drive has failed. As at late October, less than 6% of the population in African states is vaccinated against coronavirus. In many countries, including Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Ethiopia, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Nigeria and Tanzania, vaccination rates are even lower (at only around 1%), with little prospect of these picking up any time soon.

The cause of such low vaccination rates is well-known: despite recent improvements, global production continues to lag behind demand, with developing countries facing long delays in accessing vaccines.

Meanwhile, global solidarity is ineffective; so far, COVAX has shipped only around 400m doses of vaccines globally (compared with an initial target of delivering 1.9bn doses in 2021). Donations from richer countries are also failing to materialise; as at late October, developed countries had delivered only 43m doses of vaccines (out of pledges totalling about 400m — which is still far below needs).

Even if vaccines were delivered to Africa in huge quantities, this would not resolve the continent’s vaccination issues. African countries face three difficulties in rolling out inoculation programmes.

- The first is logistical, owing to a lack of transportation connections and poor cold-chain infrastructure across the continent. These factors delay the roll-out of the few shots that are received, sometimes beyond their expiry dates (Congo, Ghana, Madagascar, Malawi and South Sudan have all had to destroy expired batches of vaccines).

- The second factor is a lack of healthcare personnel to administer shots, especially in rural areas.

- A third issue has to do with vaccine hesitancy. A study by the African Union (AU) shows that, in many African countries, including Burkina Faso, the DRC, Nigeria and Senegal, vaccines against coronavirus are perceived to be “less safe” than other shots. Disinformation is at the root of this issue. In Nigeria, nearly 80% of the population believes the threat from coronavirus is “exaggerated”. In Lagos, authorities are resorting to allowing private clinics to charge high prices for vaccines, in an attempt to present them as “elite” products. Meanwhile, in Burkina Faso, 42% of the population believes that coronavirus was “planned by a foreign actor”, and half of the population is convinced that Africans are being used as “guinea pigs”. Looking forward, authorities and medical workers will face an uphill battle against these perception issues.

Originally published at http://www.eiu.com/