Health Transformation Institute (HTI)

for Digital, Health and Care Transformation

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Founder and Chief Researcher, Editor and Advisor

December, 2022

Global spending on health Rising to the pandemic’s challenges [excerpt]

World Health organization

December, 2022

Higher health spending in response to a global pandemic

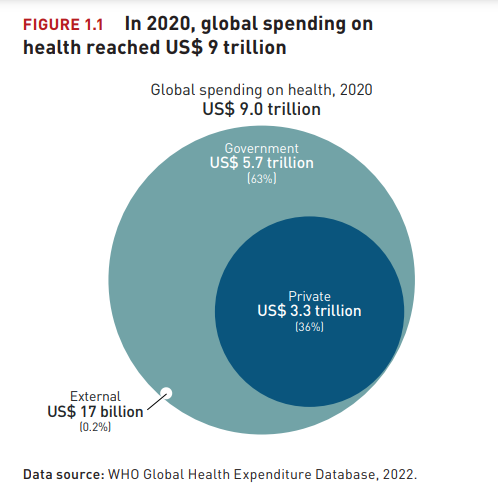

- In 2020, global spending on health reached US$ 9 trillion, or 10.8% of global gross domestic product (GDP), and was highly unequal across income groups.

- Across countries, health spending in 2020 rose in per capita terms and as a share of GDP across all income groups.

- Government spending was the main driver of the increase in total health spending from 2019 to 2020. Per capita government spending on health increased in all income groups and rose faster than in previous years.

- Health spending as a share of total government expenditure, an indicator of the priority given to health, increased from 2019 to 2020 in all income groups except high income countries.

- Out-of-pocket spending per capita fell during the first year of the pandemic, which may reflect reduced health service utilization.

- External aid continued to play a critical role in low income countries. From 2019 to 2020, per capita health spending from aid increased marginally in low income countries.

Health spending by type of service

- As expected, spending on inpatient care, outpatient care and medical goods accounted for more than 60% of total health spending in 2019 in all income groups, across the 109 countries with data. The rest was spent on preventive care, health system governance and administration, and other health services.

- In 2019, most government and donor spending on primary health care in the 18 low income countries with available data went to preventive care.

- Spending on preventive and outpatient care each accounted for more than one-third of government and donor spending on primary health care in the 26 lower-middle income countries with data.

- And spending on outpatient care accounted for more than half of government and donor spending on primary health care in the 20 upper-middle income countries with data.

- Across the 50 countries with data (29 high income, 17 middle income and 4 low income), the overall distribution of health spending by type of service in 2020 remained similar to that in 2019.

- Across the 50 countries with data, per capita total health spending rose 6% on average in real terms in 2020, though the increase varied by type of service:

o Per capita spending on inpatient care rose in 42 of the 50 countries, whereas per capita spending on outpatient care rose in nearly half of the 50 countries. On average, per capita spending on inpatient care rose 10% in real terms, and per capita spending on outpatient care rose marginally, 1%.

o Per capita spending on preventive care rose substantially, by 32% on average — and at a higher rate than total health spending in 41 of the 50 countries.

o Per capita spending on medical goods rose in around two-thirds of the 50 countries, by 3% on average.

o Spending on health system governance and administration rose in more than two-thirds of the 50 countries, by an average of 7%.

Across the 50 countries with data, per capita total health spending rose 6% on average in real terms in 2020, though the increase varied by type of service:

Health spending on COVID-19 in 2020

- Reported per capita health spending on COVID-19 from government and compulsory insurance financing arrangements in 2020 averaged US$ 212 in 16 high income countries …

- … and US$ 14 in 21 low and middle income countries with comprehensive data.

- Health spending on COVID-19 accounted for an average of about 8% of overall health spending from government and compulsory insurance financing arrangements in 2020, or 1% of general government expenditure, across 35 countries with data.

- In 15 low and middle income countries with data by source, the average share of health spending on COVID-19 in 2020 financed externally was 58% in low income countries and 28% in lower-middle income countries.

- Most reported health spending on COVID-19 from government and compulsory insurance financing arrangements in 2020 was allocated to treatment (41%) and general preventive care and administration (36%), but the types of services financed and characteristics of provision varied across countries.

- Early data from six high income countries and one lower-middle income country show that health spending on COVID-19 rose in 2021, driven by increased spending on vaccination and on testing and contact tracing.

Reported per capita health spending on COVID-19 from government and compulsory insurance financing arrangements in 2020 averaged US$ 212 in 16 high income countries …

… and US$ 14 in 21 low and middle income countries with comprehensive data.

Early data from six high income countries and one lower-middle income country show that health spending on COVID-19 rose in 2021, driven by increased spending on vaccination and on testing and contact tracing.

Government spending on health in the context of social spending

- Government spending on health does not exist in a vacuum; health spending and health outcomes are also shaped by other social spending, particularly on education and social protection.

- Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the profile of social spending in countries reflected a combination of macro-fiscal and demographic factors, as well as the government’s role in funding social services.

o Higher income countries, which typically have ageing populations, allocated a larger share of public spending to health and social protection but a lower share to education than lower income countries did. However, there is considerable heterogeneity across countries.

o Between 2000 and 2019, all three components of per capita social spending rose in real terms in high and upper-middle income countries. Health and education spending rose in lower-middle and low income countries. The trends in social protection spending in low and lower-middle income countries are unknown due to lack of data.

o While some convergence across income groups occurred in government spending on education as a share of GDP between 2000 and 2019, government spending on health became more unequal, with low income countries falling much further behind.

o A large proportion of high and upper-middle income countries reported rising health and social protection shares of government spending and declining education shares.

- During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, in high income countries, per capita health and social protection spending rose strongly, while education rose modestly.

- In upper-middle income countries, per capita health and social protection spending rose strongly while education spending fell.

- In lower-middle income countries, health spending rose strongly, while education spending remained flat.

- And in low income countries, both health and education spending rose strongly.

- The additional public debt accumulated across all income groups will present a further challenge to sustaining social spending.

The additional public debt accumulated across all income groups will present a further challenge to sustaining social spending.

Infographic

OVERVIEW [excerpt of the report]

Global expenditure on health: rising to the pandemic’s challenges

The 2022 Global Health Expenditure Report focuses on health spending in 2020, a particularly tumultuous year.

Countries around the world were simultaneously plunged into a pandemic for which few, if any, were adequately prepared.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in severe and synchronized contractions in economic output across the world.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in severe and synchronized contractions in economic output across the world.

It also compounded ongoing health system challenges and likely exacerbated existing inequalities in health and health coverage[1].

It also compounded ongoing health system challenges and likely exacerbated existing inequalities in health and health coverage[1].

Most countries rose to the pandemic’s initial challenges through exceptional budgetary allocations and reprioritization within health budgets. Globally, health spending rose to US $9 trillion in 2020, or about 10.8% of global GDP, a new high.

Most countries rose to the pandemic’s initial challenges through exceptional budgetary allocations and reprioritization within health budgets.

Globally, health spending rose to US $9 trillion in 2020, or about 10.8% of global GDP, a new high.

The increase in health spending in 2020 was driven by government spending, as average per capita public spending on health reached an all-time high in real terms across all income groups.

In contrast, out-of-pocket spending fell in per capita terms and as a share of total health spending in 2020, due possibly to lower health service utilization.

Per capita spending from external aid in low income countries in 2020 increased marginally from 2019.

In contrast, out-of-pocket spending fell in per capita terms and as a share of total health spending in 2020, due possibly to lower health service utilization.

Per capita spending from external aid in low income countries in 2020 increased marginally from 2019.

Despite the pandemic and the huge disruptions in essential health services in many countries, the composition of health spending by type of service appears to have remained broadly unchanged in 2020, based on a set of 50 countries with data, 29 of them high income.

Across all income groups, inpatient care, outpatient care and medical goods accounted for more than 60% of health spending.

Across all income groups, inpatient care, outpatient care and medical goods accounted for more than 60% of health spending.

However, per capita spending rose sharply in real terms for both preventive care (by 32%) and inpatient services (by 10%), in line with the initial prevention, detection and treatment demands of the pandemic.

However, per capita spending rose sharply in real terms for both preventive care (by 32%) and inpatient services (by 10%), in line with the initial prevention, detection and treatment demands of the pandemic.

Spending on governance and administration rose 7%, spending on medical goods rose 3% and spending on outpatient care remained stable between 2019 and 2020.

Spending on governance and administration rose 7%, spending on medical goods rose 3% and spending on outpatient care remained stable between 2019 and 2020.

The limited available data suggest that countries allocated a substantial share of public spending to COVID-19-related activities.

COVID-19-related health spending absorbed an average of 8% of government spending on health in 2020 and accounted for an average of 1% of total general government expenditure.

COVID-19-related health spending absorbed an average of 8% of government spending on health in 2020 and accounted for an average of 1% of total general government expenditure.

In high income countries, most health spending on COVID-19 went to treatment, testing and hospital care.

In contrast, in low and lower-middle income countries, most spending went to preventive measures, as well as administration and coordination of the health system.

COVID-19-related health spending absorbed an average of 8% of government spending on health in 2020 and accounted for an average of 1% of total general government expenditure.

In contrast, in low and lower-middle income countries, most spending went to preventive measures, as well as administration and coordination of the health system.

The difficulties in identifying health spending on COVID-19 mean that actual spending on COVID-19 might have been higher.

Moreover, by 2020, vaccinations were not available in most countries.

Early estimates suggest that spending on COVID-19 rose in 2021, driven by growing spending on vaccination and on testing and contact tracing.

Moreover, by 2020, vaccinations were not available in most countries.

Early estimates suggest that spending on COVID-19 rose in 2021, driven by growing spending on vaccination and on testing and contact tracing.

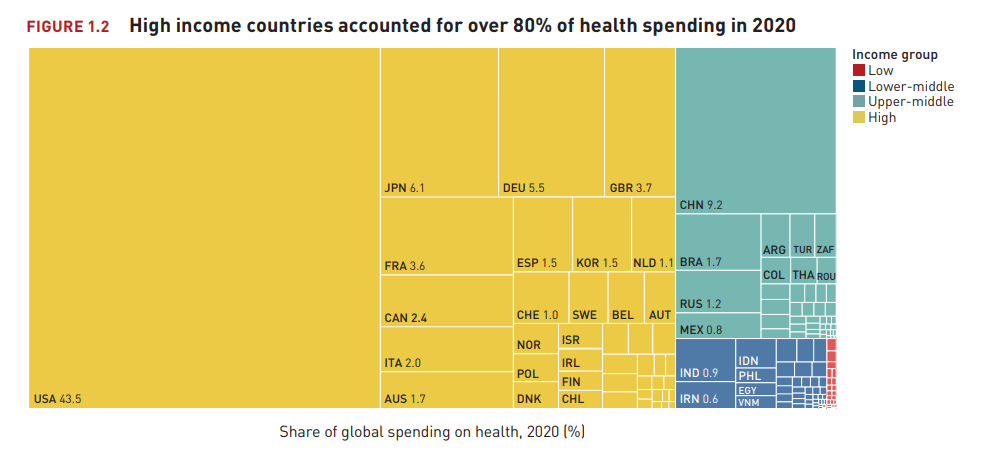

Health spending remained highly unequal across income groups in 2020 and skewed heavily towards high income countries.

Despite accounting for 15% of the world’s population, high income countries accounted for 80% of total health spending in 2020, with one country accounting for 44% of all spending.

Despite accounting for 15% of the world’s population, high income countries accounted for 80% of total health spending in 2020, with one country accounting for 44% of all spending.

- Upper-middle income countries, with 33% of the world’s population, accounted for 16% of total health spending;

- lower-middle income countries, with 43% of the world’s population, accounted for just under 4%; and

- low income countries, with 8% of the world’s population, accounted for just 0.2%.

These distributions were similar to those in 2019.

For the first time, this report examines health spending alongside other government social spending (namely, on education and social protection).

Collectively, these social spending components play a key role in supporting the well-being of the population by helping meet people’s basic day-today needs, developing and preserving human capital and providing basic security in the face of unexpected shocks.

Collectively, these social spending components play a key role in supporting the well-being of the population by helping meet people’s basic day-today needs, developing and preserving human capital and providing basic security in the face of unexpected shocks.

This broader view helps contextualize government spending on health and how it changes in response to shifting demographics, underlying macro-fiscal conditions and economic and other crises that suddenly alter demand for government spending.

The mix of social spending across countries reflects a combination of income and demographic factors and governments’ role in funding social services.

Higher income countries, which have the largest share of adults over age 65 and the smallest share of school-age children, allocated a larger share of public spending to health and social protection in 2019 but a lower share to education than lower income countries did.

Higher income countries, which have the largest share of adults over age 65 and the smallest share of school-age children, allocated a larger share of public spending to health and social protection in 2019 but a lower share to education than lower income countries did.

From 2000 to 2019, health spending became increasingly unequal, with the gap in per capita terms and as a share of GDP widening between all income groups.

From 2000 to 2019, health spending became increasingly unequal, with the gap in per capita terms and as a share of GDP widening between all income groups.

The stagnation of government health spending in low income countries has left them further behind. In contrast, government spending on education converged slightly as a share of GDP.

The stagnation of government health spending in low income countries has left them further behind. In contrast, government spending on education converged slightly as a share of GDP.

The sharp increase in government spending on health during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic was part of much broader fiscal response across all income groups in which the role of government expanded considerably.

In upper-middle, lower-middle and low income countries, the increase was driven by the large rise in government’s share of GDP and the greater priority given to health within fiscal envelopes.

In contrast, in high income countries, the increase in government spending on health was due primarily to higher overall government spending.

At the same time that health spending increased, social protection spending rose sharply in high and upper-middle income countries as governments attempted to cushion people from the economic impacts of the pandemic.

At the same time that health spending increased, social protection spending rose sharply in high and upper-middle income countries as governments attempted to cushion people from the economic impacts of the pandemic.

No consistent data on social protection spending were available for low and lower-middle income countries.

In contrast to health and social protection spending, growth in education spending was more subdued in 2020.

While governments effectively rose to the occasion during the first year of the COVID19 pandemic, the ongoing challenge is sustaining government spending on health to meet population needs.

The experiences of several decades, and now of the pandemic, have demonstrated that government spending on health is crucial to promoting universal health coverage.

Government investment in public health functions is also essential for strengthening health security.

The experiences of several decades, and now of the pandemic, have demonstrated that government spending on health is crucial to promoting universal health coverage.

Government investment in public health functions is also essential for strengthening health security.

New challenges will likely emerge as the world enters an era of rising uncertainty, complexity and volatility[2].

Against the backdrop of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, ageing populations in most countries will reshape service delivery needs.

Against the backdrop of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, ageing populations in most countries will reshape service delivery needs.

The macroeconomic consequences of the pandemic suggest not only slowing growth but also widening income inequality and growing poverty within countries[3].

The macroeconomic consequences of the pandemic suggest not only slowing growth but also widening income inequality and growing poverty within countries[3].

Moreover, new health threats will influence disease burdens and health system capacities.

This will place a greater emphasis on building stronger and more resilient health systems.

Moreover, new health threats will influence disease burdens and health system capacities.

This will place a greater emphasis on building stronger and more resilient health systems.

A key lesson of the pandemic is that health threats can have wide spillovers and jeopardize economic stability.

A key lesson of the pandemic is that health threats can have wide spillovers and jeopardize economic stability.

Additional public spending is also essential to address widening inequalities and growing poverty.

These are challenges for low income countries in particular because their fiscal capacity is generally low.

They will continue to rely on external funding to support public spending in order to ensure that poor and otherwise vulnerable people can access essential health services when needed and that the necessary investments in pandemic preparedness are made.

These are challenges for low income countries in particular because their fiscal capacity is generally low.

They will continue to rely on external funding to support public spending in order to ensure that poor and otherwise vulnerable people can access essential health services when needed and that the necessary investments in pandemic preparedness are made.

Yet as the demand for health resources rises, a combination of factors is narrowing the budgetary space available to governments.

The sharply deteriorating global macroeconomic context, with weakening income growth and rising inflation, means that governments face lower revenue and higher costs.

The sharply deteriorating global macroeconomic context, with weakening income growth and rising inflation, means that governments face lower revenue and higher costs.

This is compounding the structural challenge many countries face due to ageing populations, which reduce capacity to collect government revenues from labour markets.

This is compounding the structural challenge many countries face due to ageing populations, which reduce capacity to collect government revenues from labour markets

The large stock of additional public debt accumulated will also have ongoing budgetary implications — particularly in low and lower-middle income countries, where debt servicing is already on par with health spending.

The uncertain geostrategic situation created by the war in Ukraine exacerbates these threats through implications for the global food supply, inflation and world trade.

The uncertain geostrategic situation created by the war in Ukraine exacerbates these threats through implications for the global food supply, inflation and world trade.

The report, therefore, prompts many important questions for the next two to three years, such as:

- To what extent can governments sustain higher public spending on health and other social sectors? Will the increase in 2020 slow or be reversed — for example, due to increased debt service obligations?

- Similarly, will the decline in private health spending in 2020 continue or change? How will the pace and distribution of economic recovery within countries affect who can pay for and receive needed health services? To what extent will government efforts to support vulnerable groups enable service use while protecting against out-of-pocket spending?

- How will levels and distribution of external assistance to global public goods and country-level development assistance change given the fiscal challenges facing many high income countries?

To tackle these and other important questions, reliable policy-relevant evidence is needed.

Gaps in data on health, education and social protection spending prevent a comprehensive assessment of overall social spending patterns, especially in low and lower-middle income countries.

More detailed, accurate and widely available information on health spending would inform better investigations and policy analysis to guide future allocations to and within health systems.

Key to this is the general institutionalization of health accounts practices, in line with the global standard for the System of Health Accounts framework, at the country level.

Acknowledgements

This report is the product of the collective effort of many people around the world, led by the Health Expenditure Tracking team in WHO.

The core writing team of the report included Ke Xu, Maria Aranguren Garcia, Julien Dupuy, Natalja Eigo, Chandika Indikadahena, Joseph Kutzin, Dongxue (Wendy) Li, Lachlan McDonald, Laura Rivas, Andrew Siroka, Hapsatou Touré, Ningze Xu and Eva Zver.

WHO is grateful for the contributions of numerous individuals and agencies for their support in making this report possible. WHO thanks those who provided valuable comments and suggestions on the report:

Hélène Barroy, Sean Cockerham, Peter Cowley, Fahdi Dkhimi, Justine Hsu, Faraz Khalid, Shyama Kuruvilla, Inke Mathauer, Bruno Meessen, Susan Sparkes and Ludy Suryantoro from WHO; Anurag Kumar, Christoph Kurowski, Martin Schmidt, Denise Silfverberg and Ajay Tandon from the World Bank; Chris James, David Morgan and Michael Mueller from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); Agnes Soucat from the French Development Agency; Victoria Fan from the Center for Global Development; Nirmala Ravishankar from ThinkWell; Viroj Tangcharoensathien from the Thailand International Health Policy Program; Justice Nonvignon from the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; and global health accounts experts Patricia Hernández and Cor van Mosseveld.

WHO also wants to acknowledge the many WHO colleagues who made great contributions to the report and the data process — Kingsley Addai Frimpong, Baktygul Akkazieva, Ogochukwu Chukwujekwu, Seydou Coulibaly, Valeria De Oliveira Cruz, Tamás Evetovits, Diana Gurzadyan, Triin Habicht, Matthew Jowett, Awad Mataria, Claude Meyer, Diane Muhongerwa, Juliet Nabyonga, Benjamin Nganda, Claudia Pescetto, Tsolmongerel Tsilaajav, Lluis Vinals and Ding Wang — and global health accounts experts who helped countries prepare the data for the 2022 update of the Global Health Expenditure Database — Jean-Edouard Doamba; Evgeniy Dolgikh; Fe Vida N Dy-Liacco; Mahmoud Farag; Consulting Group Curatio Sarl, led by David Gzirishvili; Kieu Huu Hanh; Eddy Mongani Mpotongwe; Tchichihouenichidah (Simon) Nassa; Daniel Osei; Ezrah Rwakinanga; Sakthivel Selvaraj; and Neil Thalagala.

WHO also recognizes the contributions to data quality improvement by numerous World Bank staff.

The ongoing collaboration with the OECD Health Accounts Team and Eurostat has played a key role in ensuring the routine production and appropriate categorization of health spending data from most high income countries.

Most important of all, WHO extends its appreciation to the country health accounts teams and the strong support provided by the ministries of health of WHO Member States.

WHO also thanks the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; the Gavi Alliance; the United States Agency for International Development; the European Commission; the Government of Japan; the Government of the French Republic; the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office of the United Kingdom; and the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development of Canada for their funding support for WHO’s health financing work, which has played a critical role in making health spending tracking data, and the analysis of these data, a valuable global public good.

Suggested citation.

Global spending on health: rising to the pandemic’s challenges. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

References & additional information

See the original publication