This is an excerpt of the article “Your Next Hospital Bed Might Be at Home”. The post is preceded by an Executive Summary, by the Editor of the Site (Joaquim Cardoso MSc).

institute for continuous health transformation

(InHealth)

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Founder, and Chief Researcher & Editor

January 28, 2023

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

There is a potential for home-hospital care as a solution to the American health system’s lack of hospital beds and high costs.

The idea is not new, with other countries such as Australia, Canada, and several in Europe experimenting with home-hospital care for decades.

In the United States, however, the concept has faced obstacles due to the country’s complex healthcare system and culture.

In the late 1990s, a geriatrician and professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Bruce Leff, successfully conducted a pilot trial of home-hospital care for patients over 65 with straightforward diagnoses such as heart failure, emphysema, pneumonia, or a bad skin infection.

The results showed shorter stays of hospitalization and care cost about 30 percent less.

In the years that followed, Leff was able to persuade a few institutions, including a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center, to take part in a trial.

Since then, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has also funded a $9.6 million, three-year study that enabled Mount Sinai to take its hospital into the Manhattan homes of its patients who were covered by traditional Medicare.

The trial results showed that patients treated in their homes did just as well, if not better, in their homes.

The hospital-at-home movement is gaining momentum in the United States as some estimate that up to $265 billion worth of care annually for Medicare beneficiaries could be relocated to homes by 2025.

A recent report from Chartis shows that 40 percent of health executives plan to implement a hospital-at-home program in the next five years, …

… with private companies such as Medically Home, Contessa, DispatchHealth, and Sena Health moving into the home-hospital business.

These companies provide technology and management services, with some also coordinating insurance contracts.

Private insurers are also becoming more involved in providing services and reimbursements for hospital-at-home programs.

The results showed shorter stays of hospitalization and care cost about 30 percent less.

… 40 percent of health executives plan to implement a hospital-at-home program in the next five years

Private insurers are also becoming more involved in providing services and reimbursements for hospital-at-home programs.

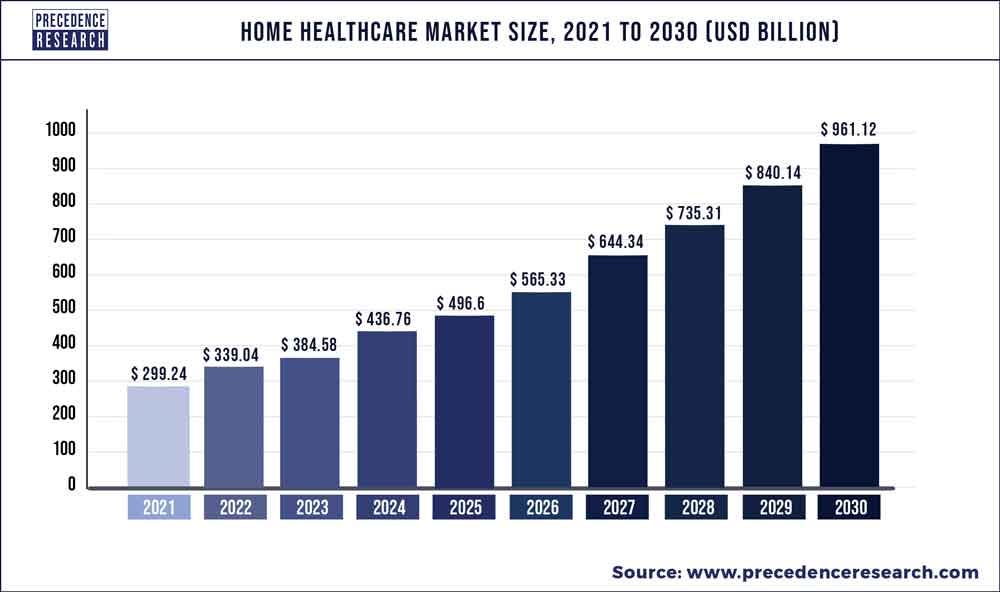

INFOGRAPHIC

- The global home healthcare market was valued at USD 299.24 billion in 2021 …

- … and is expected to reach around USD 961.12 billion by 2030 and poised to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) 13.9% during the forecast period 2022 to 2030.

DEEP DIVE

Your Next Hospital Bed Might Be at Home [excerpt]

New York Times

Helen Ouyang , Kholood Eid

January 27, 2023

The American health system needs more hospital beds.

This reality became terrifyingly palpable during the pandemic’s worst surges, when I.C.U.s and other wards were forced to turn sick people away.

In urban emergency rooms, admitted patients frequently languish for hours, sometimes even days, and occasionally in hallways, before they are moved onto inpatient floors.

The situation can be more dire in rural areas; some communities may soon be left without any hospitals at all.

In 2020, 19 rural hospitals were shuttered, more than in any year during the previous decade.

Nearly 30 percent of all rural hospitals are at risk of closing, especially tiny, stand-alone facilities.

These circumstances are likely to get worse as the baby-boomer generation continues to age, in part because of the staggering expense of hospital construction:

A new 500-bed hospital can cost more than $2 billion in some cities.

Health care in the United States is already more expensive than anywhere else in the world.

Nearly 30 percent of all rural hospitals are at risk of closing, especially tiny, stand-alone facilities.

A new 500-bed hospital can cost more than $2 billion in some cities

Hospitals aren’t even the ideal places to heal, oftentimes.

Infections spread among patients, occasionally with fatal results.

The constant alarms and beeps made by all the monitors and machinery interrupt sleep and recovery.

Older patients in particular become agitated and confused by the disruptions.

Some patients have to go through rehabilitation afterward, having been confined to a hospital bed for so long.

It’s no wonder that both patients and clinicians alike might want an alternative to traditional hospital care.

It’s no wonder that both patients and clinicians alike might want an alternative to traditional hospital care.

Presbyterian started its home-hospital after a 2005 paper in The Annals of Internal Medicine found its way to its executives’ desks.

The lead author, Bruce Leff, a geriatrician and professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, successfully conducted a pilot trial in the late 1990s. (I met Leff later, when I was a medical student there.)

With support from the John A. Hartford Foundation and the hospital leadership at Hopkins, Leff hospitalized patients in their own homes who were at least 65 and had been given one of a few straightforward diagnoses:

a worsening of their heart failure, or emphysema, pneumonia or a bad skin infection.

These patients did so well that Leff tried to spread the word by calling hospital leaders. “You kind of got the sense that people thought I had two heads,” Leff told me.

Eventually he persuaded a few institutions, including a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center, to take part in a trial.

The researchers found that patients treated in their homes had shorter stays of hospitalization and that their care cost about 30 percent less.

Because Presbyterian, like the V.A., runs its own health plan, which covers the cost of some patients’ medical services, it has more flexibility than many other hospital systems.

With Leff advising, Presbyterian was able to open hospital-at-home for patients insured through its plan.

The researchers found that patients treated in their homes had shorter stays of hospitalization and that their care cost about 30 percent less.

Because Presbyterian, like the V.A., runs its own health plan, which covers the cost of some patients’ medical services, it has more flexibility than many other hospital systems.

Other countries, including Australia, Canada and several in Europe, had already been experimenting with this practice, some of them extensively.

In Australia, which has been running home-hospitals for decades, these services provided in Victoria alone are the equivalent of what a 500-bed facility could offer in one year.

Overall, the patients treated in this way do just as well, if not better, in their homes.

In Australia, which has been running home-hospitals for decades, these services provided in Victoria alone are the equivalent of what a 500-bed facility could offer in one year.

Overall, the patients treated in this way do just as well, if not better, in their homes.

The obstacles impeding Leff and other hospital-at-home advocates in the United States were bound up with America’s labyrinthine health care system and particular medical culture.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (C.M.S.), which is the largest payer of hospitalizations, has required that nurses must be on site 24 hours a day, seven days a week, effectively keeping patients within the hospital walls.

This matches how American society has come to regard hospitalization, too — nurses at the bedside, doctors making their rounds, in elaborate facilities pulsating with machines.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (C.M.S.), which is the largest payer of hospitalizations, has required that nurses must be on site 24 hours a day, seven days a week, effectively keeping patients within the hospital walls.

But Americans didn’t always convalesce in hospitals. Before the 20th century, treatment at home was the norm.

“Only the most crowded and filthy dwellings were inferior to the hospital’s impersonal ward,” the historian Charles E. Rosenberg writes in his 1987 book “The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America’s Hospital System.”

“Ordinarily, home atmosphere and the nursing of family members provided the ideal conditions for restoring health.”

As Rosenberg puts it, “Much of household medicine was, in fact, identical with hospital treatment.”

As health care became more specialized and high-tech, however, diagnosis and treatment gradually moved into hospitals, and they evolved into institutions of science and technology.

“Ordinarily, home atmosphere and the nursing of family members provided the ideal conditions for restoring health.”

As health care became more specialized and high-tech, however, diagnosis and treatment gradually moved into hospitals, and they evolved into institutions of science and technology.

More than five years after Presbyterian began offering its services, C.M.S.’s Innovation Center funded a $9.6 million, three-year study …

… that enabled Mount Sinai to take its hospital into the Manhattan homes of its patients who were covered by traditional Medicare.

These patients suffered from a broader mix of illnesses — including hyperglycemia, blood clots and dehydration — than those in Leff’s original study.

Albert Siu and Linda DeCherrie, geriatricians at Mount Sinai and two of the trial’s leaders, bundled the hospitalization care with one month of post-discharge assistance.

They ensured that patients got to their appointments, filled their prescriptions, underwent physical therapy if needed — the sort of follow-up services that patients sometimes forget or neglect after they leave the hospital.

Albert Siu and Linda DeCherrie, geriatricians at Mount Sinai and two of the trial’s leaders, bundled the hospitalization care with one month of post-discharge assistance.

They ensured that patients got to their appointments, filled their prescriptions, underwent physical therapy if needed — the sort of follow-up services that patients sometimes forget or neglect after they leave the hospital.

The study, to which Leff contributed, showed that patients hospitalized at home were discharged two days sooner, with lower rates of E.R. visits and hospital readmissions, and that they were less likely to need rehabilitation afterward. They also gave their care higher ratings.

Though C.M.S. recognized hospital-at-home as a worthy model, the agency didn’t endorse it because it didn’t immediately save billions of dollars, …

… according to Harold Miller, the president and chief executive of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, who led the federal advisory subcommittee that evaluated the initiative.

“We have the same old system we always have, and we didn’t do anything that actually would have been desirable to do,” Miller told me with regret.

After the funding ended, Mount Sinai’s program had to find a way to get more payments to sustain its services.

At Hopkins, hospital-at-home was simply discontinued after the completion of Leff’s 16-month pilot study.

The study, to which Leff contributed, showed that patients hospitalized at home were discharged two days sooner, with lower rates of E.R. visits and hospital readmissions, and that they were less likely to need rehabilitation afterward. They also gave their care higher ratings.

After the funding ended, Mount Sinai’s program had to find a way to get more payments to sustain its services.

At Hopkins, hospital-at-home was simply discontinued after the completion of Leff’s 16-month pilot study.

But Leff, Siu and DeCherrie continued to push the idea.

They partnered with David Levine, an internist at Harvard Medical School who started Brigham and Women’s home-hospital program in Boston in 2016.

Together, the four doctors created the Hospital at Home Users Group, to share lessons learned, hold webinars and organize conferences for health systems that were interested in their own initiatives.

The intent was to spread hospital-at-home nationally, with the hope that it might eventually become a significant part of the American health care system.

The first steps in this direction had already been taken, with the proliferation of ambulatory surgery centers in the United States over the previous 50 years.

These facilities showed that patients didn’t have to stay in a hospital overnight, after all, following cataract surgery or a knee operation; they could recover in their own beds.

Surgery there costs less than in hospitals, and as C.M.S. accepted more operations on its outpatient list, more centers opened.

Recently, another important factor emerged: the spread of telehealth during the pandemic, which brought doctors into people’s living rooms.

These facilities showed that patients didn’t have to stay in a hospital overnight, after all, following cataract surgery or a knee operation; they could recover in their own beds.

Recently, another important factor emerged: the spread of telehealth during the pandemic, which brought doctors into people’s living rooms.

But the biggest catalyst has been the pandemic’s brutal impact on hospitals.

As Covid hospitalizations first swelled across the country, threatening to overwhelm hospitals, C.M.S. was forced to respond.

In March 2020, it announced that medical facilities could move hospital-level care into clinics and ambulatory surgery centers, and even into hotels and dorms.

That November, it went further, creating the Acute Hospital Care at Home waiver, temporarily allowing hospitals to treat patients in their own residences.

“It was a quick decision based on: We need to take action. We need to put solutions on the table.

The health care system can’t wait, so let’s try this,” Seema Verma, the top C.M.S. administrator at the time, told me. “In absence of that, what were they going to do, right?”

In March 2020, CMS announced that medical facilities could move hospital-level care into clinics and ambulatory surgery centers, and even into hotels and dorms.

In a matter of weeks, C.M.S. was able, with the help of experts, including some members of the Users Group, to come up with a waiver that reimbursed health systems as much for inpatient-level care in the home as in the hospital, even though room and board wasn’t being provided.

Nurses no longer had to be on site around the clock — only a minimum of two daily in-person visits by a nurse or a paramedic with additional training were required.

Verma recalls no pushback. A handful of hospitals received the C.M.S. waiver immediately, including Presbyterian, Mount Sinai and Brigham.

Suddenly, Leff’s phone was ringing off the hook with calls from hospital executives seeking advice.

The Users Group helped some of them navigate the waiver-application process.

Today more than 110 health systems, amounting to some 260 hospitals — or about 5 percent of the country’s total — have obtained the waiver.

(Geographically, the spread of home-hospital has been uneven; fewer than 10 rural hospitals have been approved so far.)

The pandemic conditions that propelled hospital-at-home programs in the United States may now be waning, but the movement itself is maintaining its momentum.

According to the consulting firm McKinsey, up to $265 billion worth of care annually being delivered in health facilities for Medicare beneficiaries — a quarter of its total cost — could be relocated to homes by 2025.

A recent report from Chartis, another consulting group, finds that nearly 40 percent of surveyed health executives intend to have implemented a hospital-at-home program in the next five years; only 10 percent or so of the respondents do not expect to develop any plan at all.

… up to $265 billion worth of care annually being delivered in health facilities for Medicare beneficiaries — a quarter of its total cost — could be relocated to homes by 2025.

… nearly 40 percent of surveyed health executives intend to have implemented a hospital-at-home program in the next five years; only 10 percent or so of the respondents do not expect to develop any plan at all.

When President Biden signed the $1.7 trillion omnibus spending bill at the end of December, the C.M.S. waiver became extended through 2024.

Currently, no official rules limit what cases can be treated at home, so long as the care meets the same standard as inpatient care in the hospital wards, but the spending bill tasks the federal government with figuring out who should be hospitalized at home.

In Leff’s vision, that could mean almost everyone eventually, improbable as that seems now.

He imagines that one day hospitals will consist only of E.R.s, I.C.U.s and specialized operating rooms.

When President Biden signed the $1.7 trillion omnibus spending bill at the end of December, the C.M.S. waiver became extended through 2024.

Currently, no official rules limit what cases can be treated at home, so long as the care meets the same standard as inpatient care in the hospital wards, but the spending bill tasks the federal government with figuring out who should be hospitalized at home.

He imagines that one day hospitals will consist only of E.R.s, I.C.U.s and specialized operating rooms.

“When hospitals build a new building, they don’t do it themselves,” Pippa Shulman, the chief medical officer of Medically Home, told me. “We are the partner when you build a home-hospital.”

Medically Home, a private company that started in 2016, has contracts with about 20 organizations, many of them signed during the pandemic.

The firm choreographs the movements of local staff and suppliers, so that tests and visits can be carried out in people’s homes; if patients become too ill, they can be easily transported back to the hospital.

Medically Home has created a technology platform to coordinate every step, so that — if everything is working right — a doctor will be able to make a computer entry and thereby prompt an action in the patient’s home as if it were being performed inside the hospital.

Medically Home has created a technology platform to coordinate every step, so that — if everything is working right — a doctor will be able to make a computer entry and thereby prompt an action in the patient’s home as if it were being performed inside the hospital.

An increasing number of companies like Medically Home have moved into the home-hospital business, among them Contessa, DispatchHealth and Sena Health.

Some firms provide only technology, like video calls or remote monitoring.

Others not only set up a hospital’s operations but also manage insurance contracts; Mount Sinai needed reimbursements after its federal grant ran out, so it partnered with Contessa to deal with insurers. (DeCherrie, one of the doctors who led Mount Sinai’s original trial, has since gone to work at Medically Home; Leff advises some of these companies.)

Consulting firms are selling their expertise to health executives.

Even private insurers are becoming more involved, not only to reimburse hospitals for the care at home but also to provide the services themselves, sometimes by working with start-ups to remove the hospital from the equation.

Their clinicians meet patients in their homes before they ever step foot in the E.R..

Their clinicians meet patients in their homes before they ever step foot in the E.R.

In April 2020, Medically Home’s first hospital client, Kaiser Permanente Northwest — which, like Presbyterian, runs its own insurance plan — opened its hospital-at-home program.

Because Oregon allows community paramedics to give in-home care, Kaiser Permanente is able to treat patients in that state using Medically Home’s nurses who are working out of a virtual command center in Massachusetts.

During a typical day, these patients can expect video calls with their doctor and nurse and in-person visits from a medic, who checks their vital signs and gives medication.

Ultrasounds, X-rays, even echocardiograms can be done in the home.

For certain problems, like wound care, nurse practitioners might trek out to a house.

The nursing and doctoring remain mostly virtual, however, unlike the treatment given through Presbyterian; a Kaiser Permanente patient might be hospitalized in his home in Longview, Wash., while his doctor is in Portland and his nurse is in Boston.

Because Oregon allows community paramedics to give in-home care, Kaiser Permanente is able to treat patients in that state using Medically Home’s nurses who are working out of a virtual command center in Massachusetts.

Ultrasounds, X-rays, even echocardiograms can be done in the home.

The nursing and doctoring remain mostly virtual, however, unlike the treatment given through Presbyterian; a Kaiser Permanente patient might be hospitalized in his home in Longview, Wash., while his doctor is in Portland and his nurse is in Boston.

In this way, Kaiser Permanente has served more than 2,000 patients in Washington and Oregon; nearly 500 more have been treated in its California program, which began in late 2020.

To put these numbers in perspective, Presbyterian’s hospital-at-home has cared for fewer than 1,600 patients since its debut 15 years ago.

Kaiser Permanente needs to operate on a scale like this, according to its executives, to offset the substantial investment that went into starting its hospital-at-home program.

“There is cost to getting these programs off the ground,” says Mary Giswold, the chief operating officer of Kaiser Permanente Northwest.

To cover them, Giswold explains, hospitals need to reach certain economies of scale.

This may be another reason C.M.S. didn’t support hospital-at-home after the Mount Sinai study:

To make financial sense, a hospital probably needs to treat at least 200 patients at home annually — a struggle for many places to reach at the time.

“There is cost to getting these programs off the ground,” …

To cover them,… hospitals need to reach certain economies of scale.

Making hospital-at-home cost-effective for health systems comes with a different kind of cost, though.

A patient may never feel the warmth of her nurse’s hand on her forehead, the reassurance of her doctor’s stethoscope over her heart.

During a video visit that I sat in on, involving Kaiser Permanente’s program, the only glimpse I caught of the patient’s home was a bottle of Tums and a mug on her side table.

When the patient noted some lower abdominal pain, the doctor couldn’t reach through the screen to examine her; instead, he had to rely on a medic’s report.

Arsheeya Mashaw, the medical director of Kaiser Permanente at Home for the Northwest, recognizes the trade-offs. “Although I’m sacrificing that bedside interaction with the patient,” Mashaw told me,

“I’m also increasing the amount of patients I can see a day to provide that better care in home to the patient, which kind of makes up for the losses.”

Critics fear that hospital-at-home may exclude those who are already marginalized — or, at the other extreme, become the only option available to those who can’t pay for their care.

Both outcomes have the potential to worsen health disparities.

“We would never not take somebody on because of the living conditions,” De Pirro told me, unless those were dangerous — a broken heater in winter, signs of domestic violence.

At Mount Sinai, patients in public housing were not only accepted into its trial; the staff took steps to address some of their other needs, like finding ways to help them afford groceries or setting up transportation services, which might otherwise have been overlooked had the patients been in a hospital room.

So far, Kaiser Permanente’s program has served a broad socioeconomic range. The recently passed federal spending package pledges to study the demographics of the people receiving this care.

Institutions also need to figure out how best to deliver these services to them.

Today the care varies widely, from Presbyterian’s in-person visits to Kaiser Permanente’s mostly virtual model. One program might send staff to check vital signs twice a day.

Another might provide round-the-clock remote monitoring through wearable technology, which worries some doctors.

“If a patient makes you nervous, and you think you want any kind of telemetry” — the continuous measurement of heart rate and rhythm — “they shouldn’t be home,” De Pirro says.

“Because the reality is if something goes wrong, what do you need to do? By the time you get them anywhere, you’re talking 20 minutes realistically.”

Some health workers cast a much harsher light on hospital-at-home’s unknowns.

“How do we learn that a program about somebody’s life and health isn’t working? That means people were injured, or people died?” asks Michelle Mahon, the assistant director of nursing practice at National Nurses United, the largest nursing union in the United States.

It strongly opposes hospital-at-home, referring to it as the “home all alone” scheme and claiming that, in the words of the union’s president, “nurses and other health professionals cannot be replaced by iPads, monitors and a camera.”

It strongly opposes hospital-at-home, referring to it as the “home all alone” scheme and claiming that, in the words of the union’s president, “nurses and other health professionals cannot be replaced by iPads, monitors and a camera.”

In the union’s view, the health care industry is seeking to exploit the pandemic for financial gain by trimming away in-person care through hospital-at-home.

Hospital executives should improve working conditions and increase nurse-to-patient ratios, Mahon says, not shift care to people’s homes.

“The answer isn’t to send in less-skilled workers, who happen to also cost less,” she says, referring to community paramedics. (A nurse’s salary can be double what a medic earns.)

Medics do not care for patients on the wards, Mahon says, so they shouldn’t do so in the home, either.

“The answer isn’t to send in less-skilled workers, who happen to also cost less,” she says, referring to community paramedics. (A nurse’s salary can be double what a medic earns.)

While the underlying cost of caring for patients in their own homes may be cheaper, the path to profit is not swift or straightforward.

Health systems, especially those that are also insurers, may eventually see sizable revenue from providing care at home.

But currently, “it’s not as if it’s a cash cow and hospital systems are making tons of money,” says Amol Navathe, a health-policy professor and internist at the University of Pennsylvania, where he is co-director of the Perelman School of Medicine’s Healthcare Transformation Institute.

That’s because of the significant upfront investment and the likelihood that reimbursement rates will go down.

Instead, Navathe says, “hospital adoption of hospital-at-home is playing defense, in a sense” — against shifting rules for reimbursement, evolving expectations among patients and start-ups that encourage people to bypass hospitals’ front doors altogether.

…“hospital adoption of hospital-at-home is playing defense, in a sense” — against shifting rules for reimbursement, evolving expectations among patients and start-ups that encourage people to bypass hospitals’ front doors altogether.

“The model is feasible, the potential is astronomical,” Navathe says, but how it fits into the American health care system is still “in the early days.”

He warns in particular that single-payer countries’ successes may not be replicated in the United States, which tends to be “much more complicated and uses a variety of different fragmented stakeholders.”

And he adds that he is skeptical that what is meant by hospital-at-home in the United States is the same as what is meant in other countries.

In Australia, for example, iron infusions could qualify, but patients would not be hospitalized for those treatments in the United States.

Even successful U.S.-based trials may not translate into real-world applications.

Though the home-hospital patients in Mount Sinai’s trial did better than the inpatient subjects, they also had 30 days of aftercare that their counterparts did not get.

And self-selection is a part of these studies; patients who go home choose to go home.

He warns in particular that single-payer countries’ successes may not be replicated in the United States, which tends to be “much more complicated and uses a variety of different fragmented stakeholders.”

Still, the health systems that have already put money into this are not likely to abandon their investments any time soon.

Kaiser Permanente and the Mayo Clinic jointly made an initial investment of $100 million in Medically Home; the three organizations have also started a coalition to advocate making the C.M.S. waiver permanent.

As part of a state-mandated performance-improvement plan, Mass General Brigham is counting on an annualized savings of $1.3 million to come from its home-hospital expansion.

It may just be that the biggest doubt about hospital-at-home is not its survival but whether it can preserve its identity as it is amalgamated into the American health care system.

Kaiser Permanente and the Mayo Clinic jointly made an initial investment of $100 million in Medically Home; the three organizations have also started a coalition to advocate making the C.M.S. waiver permanent.

“One of the things that I fret about as we try to hold hospital-at-home closer to hospital standards,” says Albert Siu of Mount Sinai, “is that we don’t want to recreate the hospital environment now in the home”

That, Siu warns, would “decrease some of the good things that we’re trying to accomplish with hospital-at-home.”

“One of the things that I fret about as we try to hold hospital-at-home closer to hospital standards,” says Albert Siu of Mount Sinai, “is that we don’t want to recreate the hospital environment now in the home”

Most rural Americans, won’t be getting hospital care at home any time soon.

In addition to the $190,000 funding from the Harvard study, A.R.H. put in close to a million dollars to jump-start its operations.

Its hospital in Hazard is big and part of an even bigger system, which all but ensures its economic viability.

For a tiny rural hospital at risk of closure, keeping its doors open while also caring for patients at home is not realistic, according to Harold Miller, the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform president, who has extensively studied and been consulted on rural hospitals.

“If they don’t have enough patients to make an inpatient unit viable, they sure as hell don’t have enough to make a hospital-at-home program viable.”

He adds, “Why you have a hospital to begin with is because you can manage more patients in a hospital than you can in multiple home sites, and the farther apart those homes are, the more challenging it is.” That describes the landscape of much of rural America.

The same staffing frustrations that trouble rural hospitals are only magnified when care moves into homes.

Fugate learned how arduous it can be when she hired six separate nurses, and every one of them failed to show up because they got better offers or realized they didn’t want to be in patients’ houses after all.

Nurses aren’t the only workers in short supply.

If paramedics fill in, then a rural community may not have anyone to respond to 911 calls.

For small rural facilities, hospital-at-home “would be cost-prohibitive, human-resource-prohibitive,” says Maria Braman, A.R.H.’s chief medical officer, now that she’s had experience building one.

“They’re barely making it,” she says. “Taking on a project like this would be impossible.”

For now, it seems hospital-at-home will share the fate of American health care generally: It’ll go to where the money is.

From multibillion-dollar medical centers, hospital-at-home will flow to those in metro areas, cities and towns, eventually making its way to patients near larger rural hospitals and then — maybe, if ever — trickling down to the people who, cruelly, already live the farthest from any hospital.

What would it take to redirect this path? “If we as a society think that hospital-at-home services are in fact desirable,” Miller says, “then they need to be paid for and covered — at whatever the cost of it is.”

About the authors & affiliations

Helen Ouyang is a physician, an associate professor at Columbia University and a contributing writer.

Her work has been a finalist for the National Magazine Award. She last wrote about how virtual reality is being used to help ease chronic pain.

Kholood Eid is a documentary photographer, filmmaker and educator based in New York and Seattle who is known for her intimate portraiture.

In 2020, she was a joint recipient of the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for Domestic Print for the Times series “Exploited.”

Originally published at https://www.nytimes.com on January 26, 2023.

Names mentioned (selected list)

Bruce Leff, a geriatrician and professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine,

Albert Siu and Linda DeCherrie, geriatricians at Mount Sinai

Harold Miller, the president and chief executive of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform

David Levine, an internist at Harvard Medical School who started Brigham and Women’s home-hospital program in Boston

Arsheeya Mashaw, the medical director of Kaiser Permanente at Home for the Northwest

Michelle Mahon, the assistant director of nursing practice at National Nurses United,

Amol Navathe, a health-policy professor and internist at the University of Pennsylvania

Seema Verma, the top C.M.S. administrator at the time

Mary Giswold, the chief operating officer of Kaiser Permanente Northwest

Maria Braman, A.R.H.’s chief medical officer,