Exposure to long working hours (≥55 hours/week) is a prevalent occupational risk factor, attributable for a large number of deaths and DALYs due to ischemic heart disease and stroke.

In 2016, 488 million people were exposed to the risks of working long hours.

Between 2000 and 2016, the number of deaths from heart disease due to working long hours increased by 42%, and from stroke by 19%,

NPR

BILL CHAPPELL

May 17, 2021

Working long hours poses an occupational health risk that kills hundreds of thousands of people each year, the World Health Organization says.

People working 55 or more hours each week face an estimated

- 35% higher risk of a stroke and a

- 17% higher risk of dying from heart disease,

compared to people following the widely accepted standard of working 35 to 40 hours in a week, the WHO says in a study that was published Monday in the journal Environment International.

“No job is worth the risk of stroke or heart disease,” WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said, calling on governments, businesses and workers to find ways to protect workers’ health.

The global study, which the WHO calls the first of its kind, found that in 2016, 488 million people were exposed to the risks of working long hours.

In all, more than 745,000 people died that year from overwork that resulted in stroke and heart disease, according to the WHO.

“Between 2000 and 2016, the number of deaths from heart disease due to working long hours increased by 42%, and from stroke by 19%,” the WHO said as it announced the study, which it conducted with the International Labour Organization.

The study doesn’t cover the past year, in which the COVID-19 pandemic thrust national economies into crisis and reshaped how millions of people work.

But its authors note that overwork has been on the rise for years due to phenomena such as

- the gig economy and

- telework —

and they say the pandemic will likely accelerate those trends.

“Teleworking has become the norm in many industries, often blurring the boundaries between home and work,” Ghebreyesus said.

“In addition, many businesses have been forced to scale back or shut down operations to save money, and people who are still on the payroll end up working longer hours.”

- Also, recessions like the one the world has seen in the past year are commonly followed by a rise in working hours, the researchers said.

The study found

- the highest health burdens from overwork in men and in workers who are middle-age or older.

- Regionally, people in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific region had the most exposure to the risk.

- People in Europe had the lowest exposure.

- In the U.S., less than 5% of the population is exposed to long work hours, according to a map the WHO published with the study.

- That proportion is similar to Brazil and Canada — and much lower than Mexico and in countries across most of Central and South America.

Several steps could help ease the burden on workers, the study states, including

- governments adopting and enforcing labor standards on working time.

- The authors also say employers should be more flexible in scheduling, and to agree with their employees on a maximum number of working hours.

- In another step, the study suggests workers arrange to share hours so no one is working 55 or more hours in a week.

To compile the report, researchers reviewed and analyzed dozens of studies on heart disease and stroke.

They then estimated workers’ health risks based on data drawn a number of sources, including more than 2,300 surveys on working hours that were conducted in 154 countries from the 1970s through 2018.

Originally published at https://www.npr.org on May 17, 2021.

Names Cited

WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesu

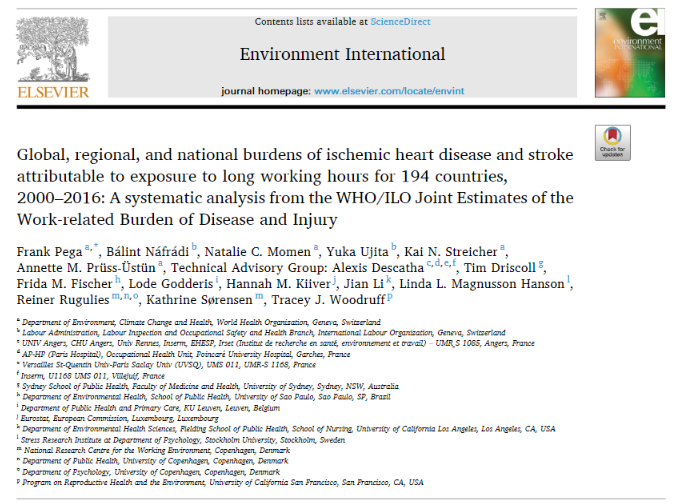

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000–2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury

FrankPega: Balint Nafradi; Natalie C. Momen; Yuka Ujita; Kai N. Streicher; Annette M. Prüss-Üstün; AlexisDescathaTim DriscollFrida M. FischerLode GodderisHannahM. KiiverJian LiLindaL. MagnussonHansonReinerRuguliesKathrineSørensenTraceyJ. Woodruff

Volume 154, September 2021, 106595

Highlights

•We present the first WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury.

•Globally in 2016, 488 million people were exposed to long working hours (≥55 hours/week).

•This exposure had 745,194 attributable deaths and 23.3 million DALYs from ischemic heart disease and stroke.

•These are 4.9% of all deaths and 6.9% of all DALYs from these causes.

•The Western Pacific, South-East Asia, men, and older people carried higher burdens.

Find below an excerpt of the long version of the paper.

ABSTRACT

Background

World Health Organization (WHO) and International Labour Organization (ILO) systematic reviews reported sufficient evidence for higher risks of ischemic heart disease and stroke amongst people working long hours (≥55 hours/week), compared with people working standard hours (35–40 hours/week).

This article presents WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of global, regional, and national exposure to long working hours, for 194 countries, and the attributable burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke, for 183 countries, by sex and age, for 2000, 2010, and 2016.

Methods and Findings

We calculated population-attributable fractions from estimates of the population exposed to long working hours and relative risks of exposure on the diseases from the systematic reviews. The exposed population was modelled using data from 2324 cross-sectional surveys and 1742 quarterly survey datasets. Attributable disease burdens were estimated by applying the population-attributable fractions to WHO’s Global Health Estimates of total disease burdens.

Results

In 2016, 488 million people (95% uncertainty range: 472–503 million), or 8.9% (8.6–9.1) of the global population, were exposed to working long hours (≥55 hours/week).

An estimated 745,194 deaths (705,786–784,601) and 23.3 million disability-adjusted life years (22.2–24.4) from ischemic heart disease and stroke combined were attributable to this exposure.

The population-attributable fractions for deaths were 3.7% (3.4–4.0) for ischemic heart disease and 6.9% for stroke (6.4–7.5); for disability-adjusted life years they were 5.3% (4.9–5.6) for ischemic heart disease and 9.3% (8.7–9.9) for stroke.

Conclusions

WHO and ILO estimate exposure to long working hours (≥55 hours/week) is common and causes large attributable burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke.

Protecting and promoting occupational and workers’ safety and health requires interventions to reduce hazardous long working hours.

Keywords

Burden of disease; Working hours; Ischemic heart disease; stroke

1. Introduction

The protection and promotion of occupational and workers’ safety and health requires actions to prevent exposures to occupational risk factors.

One such occupational risk factor is exposure to long working hours.

The very first International Labour Standard, Hours of Work (Industry) Convention, 1919 (№1) (1st International Labour Conference, 1919), and several other international labour standards (International Labour Organization, 2019a) adopted since have limited hours of work.

In 2019, countries renewed their commitment to ensuring maximum limits on working time in the Centenary Declaration on the Future of Work (International Labour Organization, 2019b).

The Hours of Work (Industry) Convention provides that the working hours of employed persons shall not exceed 8 hours/day and 48 hours/week (with some exceptions).

In some countries, however, the definition of long working hours depends on national regulations.

Nevertheless, many countries define standard working hours as 35–40 hours/week and working ≥41 hours/week as overtime work (International Labour Organization, 2017).

Occupational epidemiologists often categorize long working hours into the three analytical categories of

- 41–48,

- 49–54, and

- ≥55 hours/week,

and compare these to standard working hours (35–40 hours/week) (Descatha et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020a).

After average working time decreased steadily over the second half of the 20th century in most countries, this overall downward trend ceased and even began to reverse in some countries during the 21st Century (Messenger, 2018).

As new information and communication technologies revolutionize work, working time is predicted to further increase for some industries (Messenger, 2018).

The Hours of Work (Industry) Convention provides that the working hours of employed persons shall not exceed 8 hours/day and 48 hours/week (with some exceptions).

Evidence from previous studies suggests working long hours can increase mortality and morbidity from ischemic heart disease and stroke through psychosocial stress.

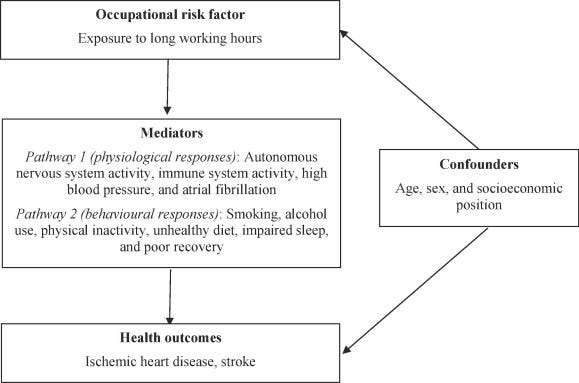

Two primary causal pathways are conceivable (Fig. 1).

- The first is through biological responses to psychosocial stress: release of excessive stress hormones due to working long hours (Chandola et al., 2010, Jarczok et al., 2013, Nakata, 2012) may trigger functional dysregulations in the cardiovascular system and structural lesions (Kivimäki and Steptoe, 2018).

- The second pathway is through behavioral responses to stress that are established cardiovascular risk factors, including tobacco use, harmful alcohol use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and resultant impaired sleep (Sonnentag et al., 2017, Taris et al., 2011, Virtanen et al., 2009).

Fig. 1. Conceptual model of the possible causal relationship between exposure to long working hours and ischemic heart disease and stroke. Footnote: Adapted from Li et al. (2020a) and Descatha et al. (2020). Some variables in this conceptual model, such as smoking and physical inactivity, could be confounders, mediators or both at the same time.

Some long working hours categories are associated with a higher risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke events.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), supported by large Working Groups of individual experts, have conducted systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the relative risks of ischemic heart disease (Li et al., 2020a) and stroke (Descatha et al., 2020) among persons working 41–48, 49–54, and ≥55 hours/week, compared with persons working 35–40 hours/week (Table 1).

Confounding was considered by, at least, sex, age, and an indicator of socioeconomic status (SES; e.g., income, education, or occupational grade).

The Working Groups of individual experts judged there to be sufficient evidence that working ≥55 hours/week is associated with a higher risk of both ischemic heart disease and stroke, compared with working 35–40 hours/week (Table 1).

To our knowledge, these are the first systematic reviews on these topics that are based on pre-published protocols (Descatha et al., 2018, Li et al., 2018); applied a dedicated systematic review framework (the Navigation Guide; Woodruff et al., 2011); and formally proceeded to assess quality and strength of evidence based on pre-published criteria and methods.

Table 1. Bodies of evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effect of exposure to long working hours on ischemic heart disease and stroke, by long working hours category.

See the long version

Countries, along with relevant international and regional organizations, and social partners, would benefit from accurate and transparent estimates of long working hours exposure and the attributable burden of disease.

These provide the evidence base for designing, developing, planning, costing, implementing, and evaluating legislation, regulations, policies, programmes, and interventions to mitigate occupational risk factor exposure and its attributable disease burden.

This article presents WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury (WHO/ILO Joint Estimates). These are estimates of exposures to long working hours (≥55 hours/week), for 194 countries, and those of the burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to these, for 183 countries. All estimates are reported at the global, regional (WHO regions), and national levels, by sex and age group, for the years 2000, 2010, and 2016.

2. Materials and methods

See the original publication

3. Results

Global health estimates for 2016 are summarized in this article. Estimates for 2000 and 2010 are found in Table 4, Table 5, regional estimates are displayed in Tables S6–S10 in Supplementary data 1, and country estimates are available on www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/monitoring/who-ilo-joint-estimates/ and http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/.

Here, regional estimates are reported for the six WHO regions (Africa, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, Europe, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific); however, with estimates for each country available, estimates could be based on any regional clustering, including the five ILO regions (Africa, Americas, Arab States, Asia and the Pacific, and Europe and Central Asia).

Table 4. Proportion of population exposed to long working hours (≥55 hours/week), 2000, 2010, and 2016, and mean percentage change for 2000–2010, 2010–2016, and 2000–2016, by sex, 194 countries.

See the original publication

3.1. Estimates of population exposed to long working hours (≥55 hours/week)

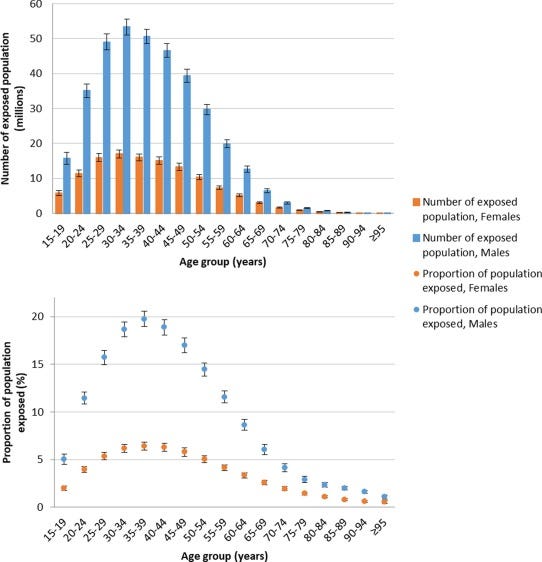

Globally in 2016, 488 million people (UR 472–503), or 8.9% of the population (UR 8.6–9.1), worked ≥55 hours/week (Table 4). A full set of estimates can be found elsewhere (www.who.int/groups/who-ilo-joint-estimates and http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/). Males and adults of early middle-age were more commonly exposed (Fig. 2). Between 2000 and 2016, the global prevalence of this exposure category increased by 9.3% (UR 4.3–14.6) (Table 4).

Fig. 2. Number of exposed population and proportion of population exposed to long working hours (≥55 hours/week), by sex and age group, 2016, 194 countries.

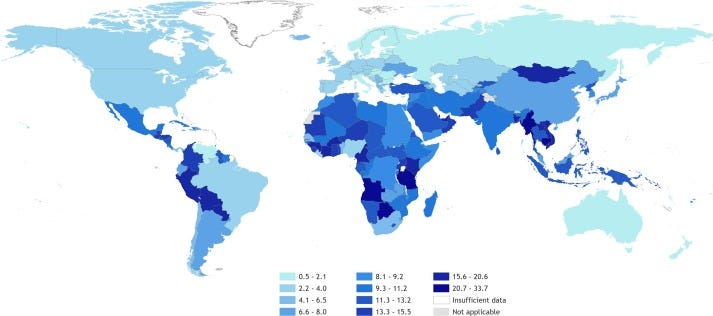

In 2016, regional exposure prevalence was largest for South-East Asia (11.7%, UR 10.8–12.5), and lowest in Europe (3.5%, UR 3.5–3.6) (Table S6; Supplementary data 1). Over the 2000–2016 period, the Western Pacific had the largest regional increase; prevalence decreased most in Africa. A map of the proportion of population exposed by country is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Proportion (%) of population exposed to long working hours (≥55 hours/week), 2016, 194 countries.

3.2. Burden of disease attributable to exposure to long working hours (≥55 hours/week)

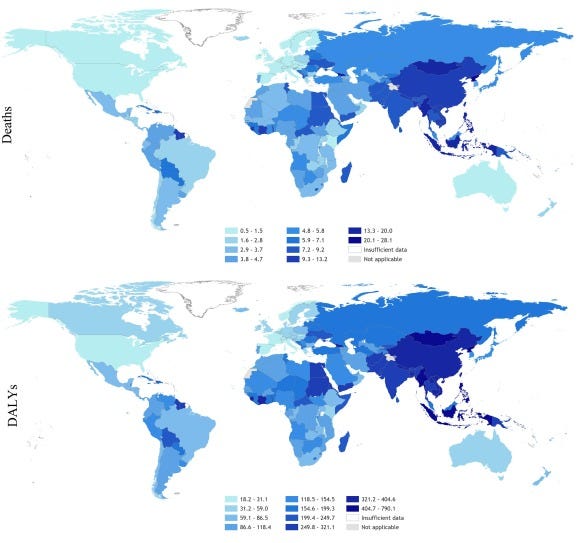

In total, an estimated 745,194 deaths (UR 705,786–784,601) and 23.3 million DALYs (UR 22.2–24.4) from ischemic heart disease and stroke combined were attributable to long working hours exposure globally in 2016. This was roughly equal between the two causes, with ischemic heart disease and stroke accounting for 46.5% and 53.5% of estimated deaths, respectively. Fig. 4, Fig. 5 present maps of the rates of deaths and DALYs from ischemic heart disease and stroke that are attributable to exposure to long working hours by country.

Fig. 4. Rate of deaths (per 100,000 of population) and DALYs (per 100,000 of population) from ischemic health disease attributable to exposure to long working hours (≥55 hours/week), 2016, 183 countries. Footnote: No estimates were produced for Andorra, Cook Islands, Dominica, Marshall Islands, Monaco, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Saint Kitts and Nevis, San Marino, and Tuvalu, because the envelopes for the burdens of ischemic heart disease were unavailable for these countries (World Health Organization, 2018b).

Fig. 5. Rate of deaths (per 100,000 of population) and DALYs (per 100,000 of population) from stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours (≥55 hours/week), 2016, 183 countries. Footnote: No estimates were produced for Andorra, Cook Islands, Dominica, Marshall Islands, Monaco, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Saint Kitts and Nevis, San Marino, and Tuvalu, because the envelopes for the burdens of stroke were unavailable for these countries (World Health Organization, 2018b).

3.2.1. Burden of ischemic heart disease attributable to exposure to long working hours (≥ 55 hours/week)

3.2.1.1. Deaths

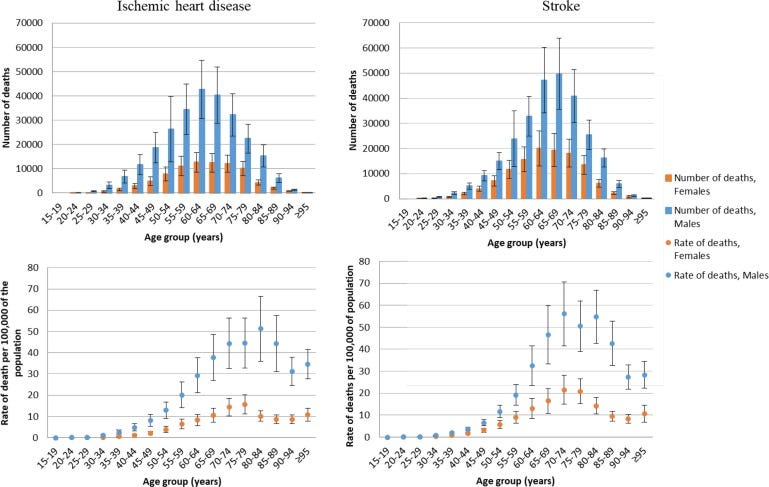

Globally in 2016, an estimated total of 9,401,800 ischemic heart disease deaths occurred. Of these, 346,753 (UR 319,658–373,848) were attributable to exposure to long working hours (Table 5). Thus, the PAF is 3.7% (UR 3.4–4.0). Males carried a larger burden, and numbers and rates of deaths increased with age up to 70 years (Fig. 6). Between 2000 and 2016, the numbers of ischemic heart disease deaths attributable to exposure to long working hours increased substantially by 41.5% (UR 27.9–56.5) (Table 5). The PAF was 3.5% (UR 3.3–3.7), 3.6% (UR 3.4–3.9), and 3.7% (UR 3.4–4.0), in 2000, 2010, and 2016, respectively. The upward trend in number of these attributable ischemic heart disease deaths was therefore driven by the increase in the total disease burden envelope, rather than an increase in the exposure.

Fig. 6. Number of deaths and rate of death (per 100,000 of population) for ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours (≥55 hours/week), by age group, 2016, 183 countries.

Of all WHO regions in 2016, South-East Asia had the largest number of ischemic heart disease deaths attributable to exposure to long working hours (159,832 deaths, UR 135,442–184,242; Table S8 in Supplementary data file 1). Africa had the lowest (16,942 deaths, UR 15,878–18,005).

3.2.1.2. DALYs

Globally in 2016, of the 202.8 million DALYs lost from ischemic heart disease in total, 10.7 million DALYs (UR 9.9–11.4) were attributable to exposure to long working hours (Table 5). Between 2000 and 2016, attributable DALYs increased by 41.2% (UR 28.5–54.6). In 2000, 2010, and 2016, the PAF was 4.8 (UR 4.5–5.1), 5.1 (UR 4.7–5.4), and 5.3 (UR 4.9–5.6), respectively (Table 6).

Table 6. Population-attributable fraction (PAF) for deaths and DALYs from ischemic heart disease and stroke, attributable to exposure to long working hours (≥55 hours/week), 2000, 2010, and 2016, by sex, 183 countries.

See the original publication

3.2.2. Burden of stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours (≥55 hours/week)

3.2.2.1. Deaths

Globally, stroke caused an estimated 5,747,289 deaths in 2016. Of these, 398,441 (UR 369,826–427,056) were attributable to exposure to long working hours (Table 5). Thus, the PAF was 6.9% (UR 6.4–7.5). Both in absolute and relative terms, males and older age groups (60–74 years) carried a larger burden (Fig. 6). Over 2000–2016, the total number of stroke deaths attributable to exposure to long working hours increased by 19.0% (UR 7.8–31.1) (Table 5). The PAF was 6.5% (UR 6.1–7.0), 6.8% (UR 6.3–7.3), and 6.9% (UR 6.4–7.5), in 2000, 2010, and 2016, respectively (Table 6). The upward trend in number of attributable stroke deaths was therefore also primarily driven by the increase in the total disease burden envelope.

The largest number of deaths regionally was estimated for South-East Asia (158,987 deaths, UR 141,968–176,006; Table S10 in Supplementary file 1). The lowest number was for the Americas (18,285 deaths, UR 17,162–19,409).

3.2.2.2. DALYs

Globally in 2016, of the 135.9 million DALYs lost from stroke, 12.6 million (UR 11.8–13.4) were attributable to exposure to long working hours (Table 5), up by 21.7% from 2000 (UR 11.8–32.4). In 2000, 2010, and 2016, the PAF was 8.6 (UR 8.1–9.1), 9.0 (UR 8.5–9.5), and 9.3% (UR 8.7–9.9), respectively (Table 6).

3.3. Sensitivity analyses

Results from sensitivity analyses showed that despite some variation in estimates, number of deaths and DALYs remained appreciable when the assumed lag time was reduced to 8 years and increased to 12 years and when the time window was reduced to 8 years and increased to 12 years (Table S11; Supplementary file 1). Assigning the most common exposure category, rather than the highest one, however, reduced the deaths and DALYs substantially.

4. Discussion

This article presented WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of exposure to long working hours and the attributable burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke.

- In summary, in 2016, 8.9% of the global population were exposed to working ≥55 hours/week.

- An estimated 745,194 deaths and 23.3 million DALYs from ischemic heart disease and stroke combined were attributable to this occupational risk factor.

Of all deaths from ischemic heart disease and stroke in 2016,

- 3.7% and 6.9% were attributable to exposure to working long hours;

- as were 5.3% and 9.3% of all DALYs from ischemic heart disease and stroke.

The disease burdens were disproportionately higher

- in the South-East Asian and Western Pacific regions,

- men, and

- people of middle to older working age.

Between the years 2000 and 2016,

- the exposed population increased by 9.3%,

- and the attributable burdens of deaths from ischemic heart disease and stroke increased by 41.5% and 19.0%, respectively.

4.1. Comparison with previous findings and interpretations

The distribution in the population and trends over time in the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of exposure to long working hours are consistent with recent ILO analyses of population distributions and time trends observed in official survey data on working time (Messenger, 2018).

To our knowledge, there are no prior estimates of burden of disease attributable to exposure to long working hours that we could compare these first WHO/ILO Joint Estimates against.

These WHO/ILO Joint Estimates demonstrate that the disease burden attributable to exposure to long working hours is the largest of any occupational risk factor calculated to date, compared with those attributable to other occupational risk factors included in global Comparative Risk Assessments (GBD 2016 Occupational Risk Factor Collaborators, 2019, World Health Organization, 2016).

The population prevalence of exposure to long working hours increased substantially between 2010 and 2016.

If this trend continues, it is likely that the population exposed to this occupational risk factor will expand further. Potential reasons for this include expansion of the gig economy (Messenger, 2018), the uncertainty introduced, and new working-time arrangements (e.g., on-call work, telework, and the platform economy).

Past experience has shown that working hours increased after previous economic recessions (Bloom, 2009); such increases may also be associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Estimated increases in exposure have been largest in South-East Asia and the Western Pacific. Furthermore, the total envelopes of the burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke are also increasing rapidly.

As both exposed population and total disease burden expand, the burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke that can be attributed to exposure to working long hours may therefore also be expected to increase.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

WHO and ILO have produced a detailed set of estimates of the burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours. These estimates were based on systematic reviews and meta-analyses of evidence to date. Multiple data sources provided large samples from all regions to calculate estimates.

However, the study has some limitations, which should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the systematic reviews and meta-analyses estimated relatively small increases in risk, even where statistical significance is reached. Evidence comes from observational studies, for which residual confounding cannot be ruled out, and we cannot be certain that a causal association exists; however most of the high-quality evidence came from prospective cohort studies which took steps to reduce confounding and will be more representative of population risk. Taking this into consideration, the Working Group of individual experts rated the evidence as of “moderate quality” and as “sufficient evidence for harmfulness” (Descatha et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020a) for the exposure category ≥55 hours/week for both ischemic heart disease and stroke. Other researchers have disagreed with the rating of the Working Group that there is “sufficient evidence for harmfulness” of long working hours with regard to ischemic heart disease (Kivimäki et al., 2020). The Working Group has acknowledged this disagreement and has elaborated why the assigned rating is supported by the evidence (Li et al., 2020b).

Second, it has been argued that, at least with regard to ischemic heart disease, not only length of working hours, but also the quality of the work in which persons spend their hours, may be of importance (Kivimäki et al., 2020). Although Kivimäki et al. (2020) presented data and the Working Group of individual experts conducted analyses stratified by SES that suggested a trend for stronger associations between exposure to long working hours and risk of ischemic heart disease among individuals of lower SES (Li et al., 2020a), these were limited to studies from high-income countries and one region only (Europe). The Working Group deemed the evidence for a possible effect modification of SES in the association between long working hours and ischemic heart disease as inconclusive for a global study (Li et al., 2020a, Li et al., 2020b). Currently, evidence does not support producing such global health estimates disaggregated by SES; however more research is needed in additional and more diverse countries and regions on the roles of SES and work quality for the association of long working hours with health outcomes.

Third, quality of data on both long working hours and burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke will vary by source. Most data regarding long working hours were obtained from national statistics offices with established, official data collection protocols (e.g., statistical standards), but variation can still be expected. All surveys used self-reported data on working hours. Several studies showed both reliability and validity of self-reported hours, compared with administrative records (Imai et al., 2016, Saunders et al., 2005, Todd et al., 2010); however, this may vary. This could lead to under- or over-estimations of the burden, depending on the direction of the error.

Fourth, several assumptions were made during modelling. While they were based on current knowledge and transparently described in detail (Table 3), these may need review as more evidence becomes available. In addition, as noted above, we provide policy makers with alternative scenarios through sensitivity analyses. While changes to the assumed lag time and time window, in the sensitivity analyses, resulted in some variation from the main results, a relatively large reduction in attributable deaths and DALYs were seen when the most common exposure category was used, rather than the highest. As described in Table 3, the highest exposure category was used as risks from exposures can remain, even when exposure levels are reduced, for diseases with long latency periods. However, this may have resulted in overestimation of health loss attributable to exposure to long working hours. Assignment of the highest exposure category (as in our main analysis) is the standard practice in burden of disease estimation studies; however, by providing additional information for policy making, sensitivity analyses of estimates with the most common exposure category assigned, we show that if this exposure assignment was to be found to be evidence-based, then this would be the estimated disease burden, adding further transparency through adding another scenario.

Fifth, there are additional factors likely to affect both working hours and disease burdens, which were not considered in these analyses (e.g., shift work), but could be considered in future cycles of the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates (Li et al., 2020b). Seasonal variations could be a factor for some occupations (e.g., agricultural workers). For some countries longitudinal survey data were available, for which quarterly surveys took data from an individual over multiple time points. When these data were available, we took an average of the data which should mitigate some of the seasonal differences; however, the majority of the data used in the assessment of long working hours exposure were cross-sectional, so this is a limitation. There are also several potential mediators (Fig. 1), which are challenging to address (Descatha et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020a). Sixth, there may be competing risks; for example, people exposed to long working hours may die of other causes or migrate before reaching the typical ages when cardiovascular disease events occur.

5. Conclusions

WHO and ILO estimate that exposure to long working hours (≥55 hours/week) is a prevalent occupational risk factor, attributable for a large number of deaths and DALYs due to ischemic heart disease and stroke.

In the global Comparative Risk Assessment, it is currently the occupational risk factor with the largest attributable disease burden.

These first WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury provide the basis for actions to prevent exposure to hazardous long working hours and thereby reduce the attributable burden of ischemic heart disease and stroke, at the global, regional, and national levels, across the health and labour sectors.

This includes implementation of the international labour standards on working time, such as setting standards on working time limits (International Labour Organization, 2019a, International Labour Organization, 2019b).

Legislation, regulations, policies, programmes, and interventions on working time arrangements must ensure that the setting, monitoring, and enforcement of hours of work and the number of additional hours performed by workers occur within a framework that does not harm human health (Landsbergis, 2018, Messenger, 2018).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Frank Pega: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing — original draft, Supervision, Writing — review & editing. Bálint Náfrádi: Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing — review & editing. Natalie C. Momen: Visualization, Writing — review & editing. Yuka Ujita: Writing — review & editing. Kai N. Streicher: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing — review & editing. Annette M. Prüss-Üstün: Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing — review & editing. Technical Advisory Group: Methodology, Writing — review & editing.

References

See the original publication

originally published at https://www.sciencedirect.com