This is an excerpt of the publication below, with the title above, focusing on the topic in question.

Global Horizons for Value-Based Care: Lessons Learned from the Cleveland Clinic

NEJM Catalyst

Chibueze Okey Agba, MBA, Joshua Snowden-Bahr, JD, MHA, Kushal T. Kadakia, MSc, Samer Abi Chaker, MD, MPH, James B. Young, MD, and Alex G. Forystek

June 28, 2022

One page summary by:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Health Transformation Institute

Continuous transformation for universal health

Value Based Care Unit

July 5, 2022

Overview:

- The Cleveland Clinic describes the lessons it has learned from working with value-based care models in the U.S., the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.

Summary

- The full version of this article reviews the Cleveland Clinic’s unique experience developing, operating, and refining value-based care models

(1) in the United States and

(2) The United Arab Emirates, with early applications and lessons learned

(3) in the United Kingdom,

… using these case studies to extrapolate challenges, successes, and opportunities for implementing global value-based care models.

Discussion

- Health care as an industry has at least a theoretical commitment to continuous improvement.

- However, one must distinguish between activities that are value- added and models that are value- based, with value previously defined as outcomes per dollar spent.

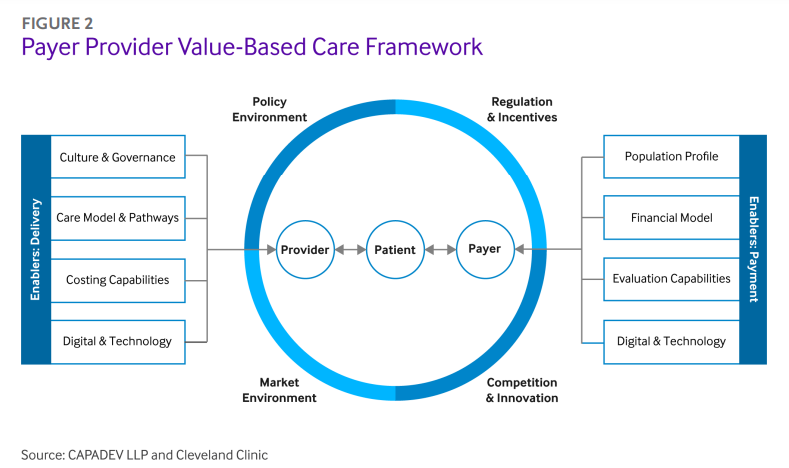

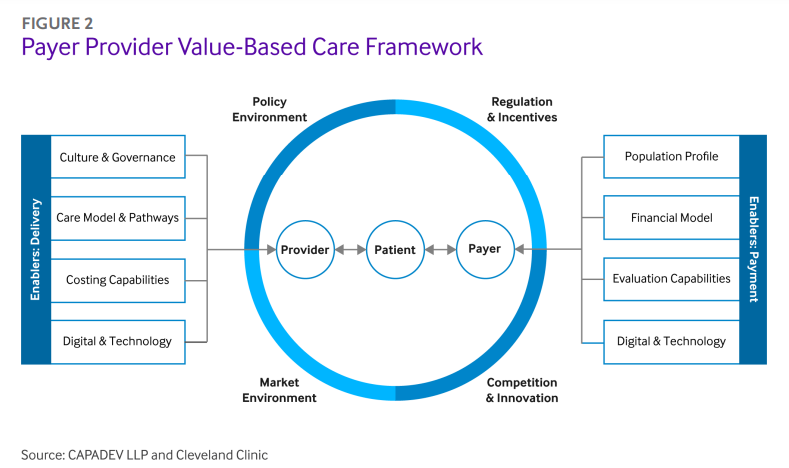

- As illustrated in Figure 2, value-based care models must be patient-centered, with cost, quality, and outcomes mediated by the relationship between providers and payers.

- Each entity contributes respective enablers for value.

- These interactions are further influenced by the policy and market environment in the provider’s location.

What are the enablers of Value Based Care?

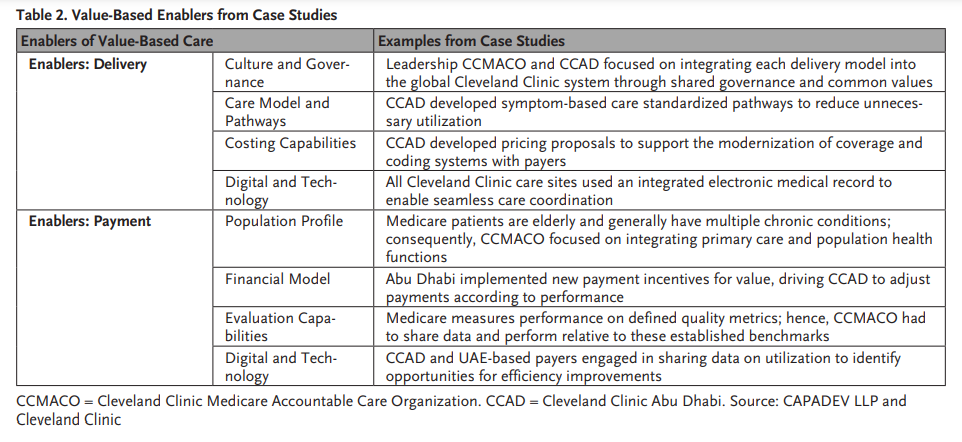

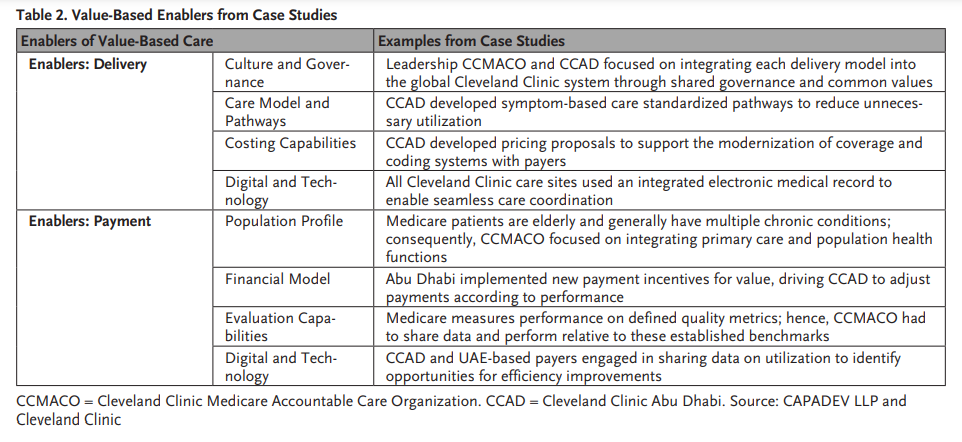

- Table 2 summarizes examples from the case studies for each of the enablers of value-based care models presented in .

- Collaborations among regulators, providers, and payers were critical for navigating local policy and market environments.

- As the value-based care framework in and the examples in Table 2 demonstrate, strategic planning, early investment in governance models (including steering committees and clinical institutes), and a long-term commitment among all parties can propagate care models to achieve the shared goals of better outcomes at a lower cost — even in environments new to value-based care and payer-provider partnerships.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (excerpt of full version)

The United States is not alone in trying to evolve more effective financial incentives for improving health care. The Cleveland Clinic describes the lessons it has learned from working with value-based care models in the U.S., the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.

Summary

As global health care expenditures continue to rise due to aging populations and managing chronic diseases, providers, payers, and policy makers must shift their focus from traditional fee-for-service models to value-based care programs.

Despite early progress in the value space, there have been delays in implementation to stand up value-based programs due to transition costs and changes to infrastructure, as well as varying health care infrastructure capabilities across the globe.

This article reviews the Cleveland Clinic’s unique experience developing, operating, and refining value-based care models in the United States and the United Arab Emirates, with early applications and lessons learned in the United Kingdom, using these case studies to extrapolate challenges, successes, and opportunities for implementing global value-based care models.

Introduction

Rising health care expenditures coupled with evolving patient needs have generated a global impetus for health care reform.

As the public sector bears an increasing proportion of costs, policy makers and health system leaders have sought to identify financing arrangements and care delivery strategies capable of reducing costs and improving population health.1

For example, in the United States (U.S.), the Affordable Care Act supported the development of payment models designed to incentivize quality and improved outcomes.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) introduced a prospective payment system to improve efficiency and enable performance comparisons across different hospitals.

In the United Kingdom (UK), the Five Year Forward View called for investment in “new care models” to support service integration.

These different reforms share the common goal of promoting high-value health care, with the best possible outcomes per dollar spent.

Translating value-based care from theory into practice remains challenging. Research evidence is still emerging and there is no consensus on an optimal approach.

From Michael Porter’s six interdependent and mutually reinforcing components in a high-value health care delivery system to a recent European publication’s identification of eight mandatory components to implement value-based health care in a hospital, proposed models differ based on elements and regional applications.

Obstacles are numerous, ranging from misaligned incentives resulting from fee-for-service payment structures, to infrastructure gaps, to burdensome regulations.

Successful models often rely on payer-provider partnerships and leverage system-level capabilities.

By changing reimbursement, providers and payers can redefine what services are considered valuable, supporting reductions in unnecessary utilization and improvements in care coordination.

However, payers and providers face barriers to coordination.

Providers may operate in incompatible payment environments, simultaneously trying to fulfill the requirements of both fee-for-service and value-based contracts, where financial incentives (payment for service volume vs. payment for “value”), expectations (e.g., financial risk), and capabilities (e.g., data sharing) differ depending on the type of contract.

Providers must reduce expenditures while still retaining the fixed costs of legacy infrastructure, which remains fragmented by specialty rather than integrated according to patient needs and evidence-based clinical guidelines.

Nevertheless, the experience of successful payer-provider partnerships reveals a basic truth about health care innovation: while good intentions can spark change, strong incentives enable change to last.

Providers must reduce expenditures while still retaining the fixed costs of legacy infrastructure, which remains fragmented by specialty rather than integrated according to patient needs and evidence-based clinical guidelines.

As the public sector bears an increasing proportion of costs, policy makers and health system leaders have sought to identify financing arrangements and care delivery strategies capable of reducing costs and improving population health.

Nevertheless, the experience of successful payer-provider partnerships reveals a basic truth about health care innovation: while good intentions can spark change, strong incentives enable change to last.

Discussion

Health care as an industry has at least a theoretical commitment to continuous improvement.

However, one must distinguish between activities that are value- added and models that are value- based, with value previously defined as outcomes per dollar spent.

As illustrated in Figure 2, value-based care models must be patient-centered, with cost, quality, and outcomes mediated by the relationship between providers and payers.

Each entity contributes respective enablers for value.

A provider’s culture and governance, care model and pathways, costing capabilities, and digital and technology functions represent enablers on the delivery side, whereas the payer’s population profile, financial model, evaluation capabilities, and digital and technology functions function as the enablers on the payment side.

These interactions are further influenced by the policy and market environment in the provider’s location.

These case studies illustrate how carefully designed and well-executed payer-provider partnerships help deliver value-based care in different clinical and cultural contexts.

Table 2 summarizes examples from the case studies for each of the enablers of value-based care models presented in .

For example, the care pathways model for CCAD represents a unique enabler for value-based delivery in the Abu Dhabi market.

Likewise, the CCMACO value-based steering committee provided an organizational culture and governance of empowering physicians to serve as leaders and cocreate the quality measures for which they would later be held accountable.

On the payment side, the evaluation capabilities of the Department of Health in Abu Dhabi enabled the transition to prospective payment and pay-for-performance.

The profile of the insured population also frames the orientation of care delivery.

For instance, because most Medicare patients are age 65+ and often have multiple chronic diseases, payers needed to calibrate financial incentives and quality measures around improving disease management.

CCMACO’s emphasis on primary care and population health impacted this important aspect of the patient journey.

Collaborations among regulators, providers, and payers were critical for navigating local policy and market environments.

For example, CCAD had to work with regulators on updating coding and coverage policies for novel technologies to address tertiary-quaternary care gaps that previously resulted in longer episodic costs or Emiratis receiving more expensive treatment outside of their home country.

As the value-based care framework in and the examples in Table 2 demonstrate, strategic planning, early investment in governance models (including steering committees and clinical institutes), and a long-term commitment among all parties can propagate care models to achieve the shared goals of better outcomes at a lower cost — even in environments new to value-based care and payer-provider partnerships.

To illustrate the generalizability of Cleveland Clinic’s experiences designing, building, and sustaining value-based care models, we offer the following four cross-cutting lessons.

- 1.Proactively Plan to Streamline Implementation

- 2.Establish a Governance Model for Value-Based Care

- 3.Develop Infrastructure and Frameworks for Data-Driven Decision-Making

- 4.Focus on the Whole Patient Journey

1.Proactively Plan to Streamline Implementation

Engaging with policy makers to help streamline regulations is critical to guide hospital networks’ approach to new geographies.

For example, in the UK, a Competition and Markets Authority investigation illustrated the need for new entrants, while in the UAE, a focus on reducing the need for UAE nationals and residents to travel overseas to receive complex treatment preceded a drive to operate under prospective environments and introduce tertiary-quaternary care provisions.

Value-based care models must be patient-centered, with cost, quality, and outcomes mediated by the relationship between providers and payers.

2.Establish a Governance Model for Value-Based Care

For value-based models to succeed, providers must clearly define and refine responsibilities, governance models, and terms of engagement when contracting with payers.

The case studies illustrate the importance of inclusive and empowered governance models to foster accountability and drive decision-making.

For example, CCMACO developed a formal legal entity for the ACO that included representation from independent providers who had entered into a partnership with Cleveland Clinic, enabling providers to support designing the performance measures for which they would ultimately be accountable.

Likewise, CCL from the outset has included committee structures in its contracts with payers with details proposing representation, developing meeting structures, and identifying action items.

3.Develop Infrastructure and Frameworks for Data-Driven Decision-Making

Infrastructure for data collection and exchange requires proactive development.

For example, Cleveland Clinic has used the same electronic medical record platform at each of its care sites, creating global connectivity.

Likewise, developing the capacity to share data across platforms and review progress at regular intervals will strengthen the partnership between payers and providers.

Providers may possess key data on clinical metrics (e.g., hospital-acquired infections), while payers may possess key data on utilization metrics (e.g., referral experience for patients).

From an implementation perspective, data sharing may pose complications, and may require navigating regulations on patient privacy (e.g., HIPAA in the U.S., the EU General Data Protection Regulation, and the UK’s own adoption of GDPR and Data Protection Act, as may be further amended post-Brexit).

Solving for these challenges from the outset prevents future roadblocks.

Lastly, not all data is made equal: measurements should be relevant, timely, informative, and actionable.

Providers and payers should create dashboards with KPIs from agreed sources of truth to measure progress and guide decision-making.

4.Focus on the Whole Patient Journey

Interest in value-based care will continue to grow as health care reforms accelerate around the world.

While payment and delivery reforms are the primary focus of value-based care, it is necessary to acknowledge the important roles of suppliers, drug and device makers, and IT developers, all of which are beyond the scope of this article.

Nevertheless, the global case studies in this article offer lessons for health care leaders from our efforts to design, implement, and sustain partnerships in different international markets.

Although the nuances of challenges and solutions for health care innovation will differ, the overarching goal should remain the same: deliver value as defined and measured ultimately with the patient at the center.

About the authors and affiliations:

Chibueze Okey Agba, MBA

Chief Financial Officer, Hartford HealthCare, Hartford, Connecticut, USA

Joshua Daniel Snowden-Bahr, JD, MHA

Regional Director, Contracting & Business Development (International Markets), Market & Network Services, Cleveland Clinic Health System, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Kushal T. Kadakia, MSc

MD Candidate, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Samer Abi Chaker, MD, MPH

Health Care Program Leader, CAPADEV LLP, Dubai, UAE

James B. Young, MD

Executive Director of Academic Affairs, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA; Professor of Medicine & Vice Dean for Academic Affairs, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Alex G. Forystek

International Payer Contracts Manager, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

References and additional information

See original publication

Originally published at https://catalyst.nejm.org on June 28, 2022.

RELATED ARTICLES