NEJM Catalyst

Chibueze Okey Agba, MBA, Joshua Daniel Snowden-Bahr, JD, MHA, Kushal T. Kadakia, MSc, Samer Abi Chaker, MD, MPH, James B. Young, MD, and Alex G. Forystek

June 28, 2022

Executive Summary by:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Health Transformation Institute

Continuous transformation for universal health

Value Based Health Care Unit

July 5, 2022

Overview:

- The United States is not alone in trying to evolve more effective financial incentives for improving health care.

- The Cleveland Clinic describes the lessons it has learned from working with value-based care models in the U.S., the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.

Summary

- As global health care expenditures continue to rise due to aging populations and managing chronic diseases, providers, payers, and policy makers must shift their focus from traditional fee-for-service models to value-based care programs.

- Despite early progress in the value space, there have been delays in implementation to stand up value-based programs due to transition costs and changes to infrastructure, as well as varying health care infrastructure capabilities across the globe.

- This article reviews the Cleveland Clinic’s unique experience developing, operating, and refining value-based care models

(1) in the United States and

(2) The United Arab Emirates, with early applications and lessons learned

(3) in the United Kingdom,

… using these case studies to extrapolate challenges, successes, and opportunities for implementing global value-based care models.

Discussion

- Health care as an industry has at least a theoretical commitment to continuous improvement.

- However, one must distinguish between activities that are value- added and models that are value- based, with value previously defined as outcomes per dollar spent.

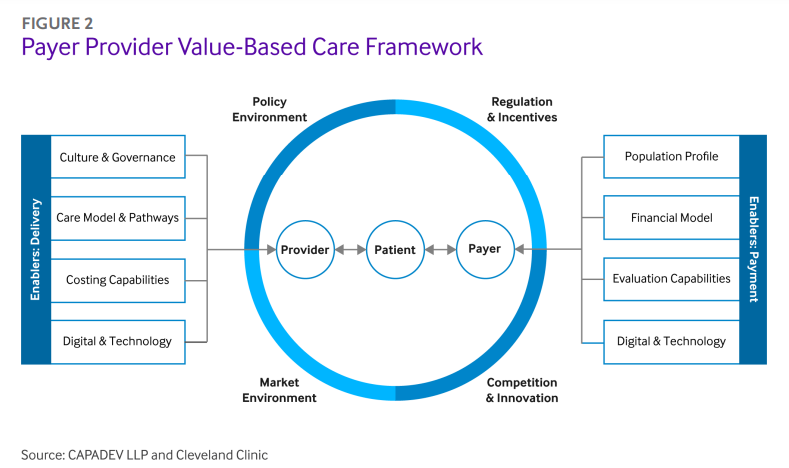

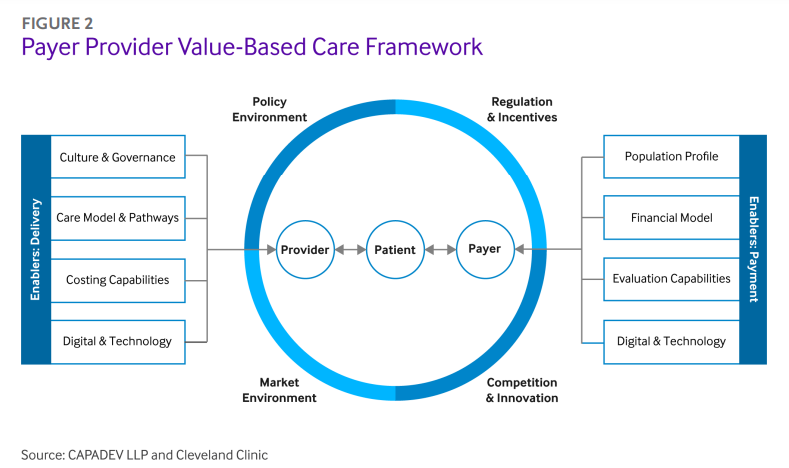

- As illustrated in Figure 2, value-based care models must be patient-centered, with cost, quality, and outcomes mediated by the relationship between providers and payers.

- Each entity contributes respective enablers for value.

- These interactions are further influenced by the policy and market environment in the provider’s location.

- These case studies illustrate how carefully designed and well-executed payer-provider partnerships help deliver value-based care in different clinical and cultural contexts.

What are the enablers of Value Based Care?

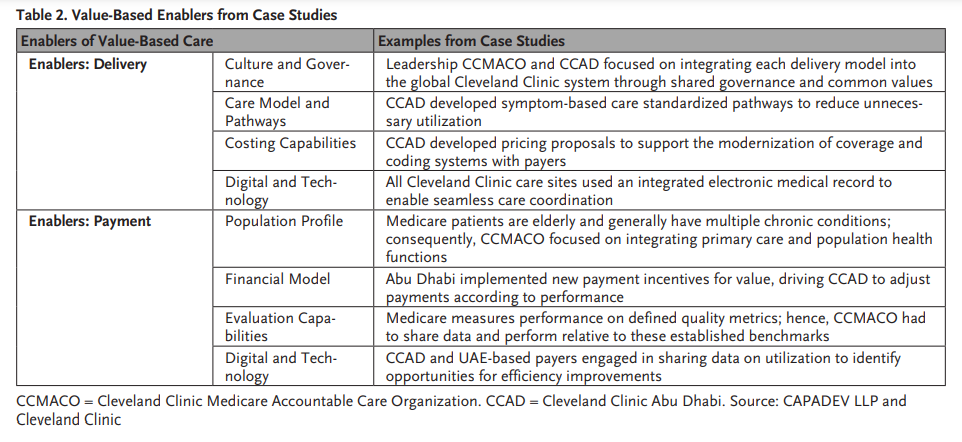

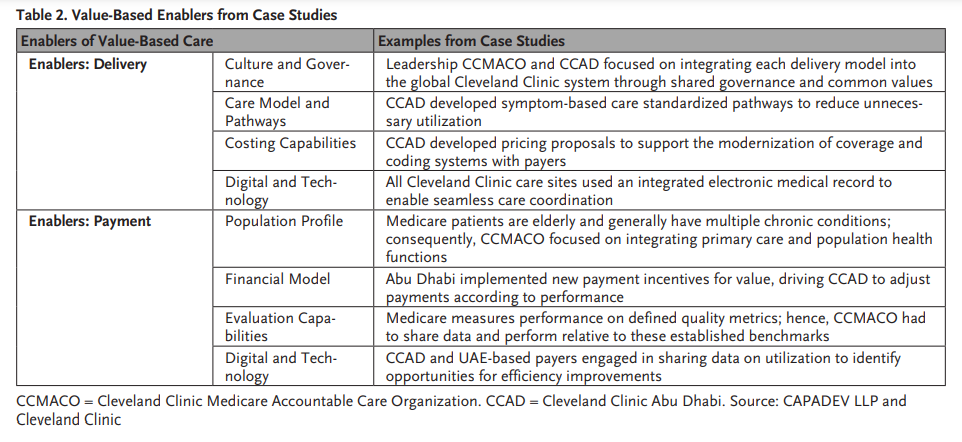

- Table 2 summarizes examples from the case studies for each of the enablers of value-based care models presented in .

- Collaborations among regulators, providers, and payers were critical for navigating local policy and market environments.

- As the value-based care framework in and the examples in Table 2 demonstrate, strategic planning, early investment in governance models (including steering committees and clinical institutes), and a long-term commitment among all parties can propagate care models to achieve the shared goals of better outcomes at a lower cost — even in environments new to value-based care and payer-provider partnerships.

What are the lessons learned?

- To illustrate the generalizability of Cleveland Clinic’s experiences designing, building, and sustaining value-based care models, we offer the following four cross-cutting lessons.

- 1.Proactively Plan to Streamline Implementation

- 2.Establish a Governance Model for Value-Based Care

- 3.Develop Infrastructure and Frameworks for Data-Driven Decision-Making

- 4.Focus on the Whole Patient Journey

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version)

The United States is not alone in trying to evolve more effective financial incentives for improving health care. The Cleveland Clinic describes the lessons it has learned from working with value-based care models in the U.S., the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.

Summary

As global health care expenditures continue to rise due to aging populations and managing chronic diseases, providers, payers, and policy makers must shift their focus from traditional fee-for-service models to value-based care programs.

Despite early progress in the value space, there have been delays in implementation to stand up value-based programs due to transition costs and changes to infrastructure, as well as varying health care infrastructure capabilities across the globe.

This article reviews the Cleveland Clinic’s unique experience developing, operating, and refining value-based care models in the United States and the United Arab Emirates, with early applications and lessons learned in the United Kingdom, using these case studies to extrapolate challenges, successes, and opportunities for implementing global value-based care models.

Introduction

Rising health care expenditures coupled with evolving patient needs have generated a global impetus for health care reform.

As the public sector bears an increasing proportion of costs, policy makers and health system leaders have sought to identify financing arrangements and care delivery strategies capable of reducing costs and improving population health.1

For example, in the United States (U.S.), the Affordable Care Act supported the development of payment models designed to incentivize quality and improved outcomes.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) introduced a prospective payment system to improve efficiency and enable performance comparisons across different hospitals.

In the United Kingdom (UK), the Five Year Forward View called for investment in “new care models” to support service integration.

These different reforms share the common goal of promoting high-value health care, with the best possible outcomes per dollar spent.

Translating value-based care from theory into practice remains challenging. Research evidence is still emerging and there is no consensus on an optimal approach.

From Michael Porter’s six interdependent and mutually reinforcing components in a high-value health care delivery system to a recent European publication’s identification of eight mandatory components to implement value-based health care in a hospital, proposed models differ based on elements and regional applications.

Obstacles are numerous, ranging from misaligned incentives resulting from fee-for-service payment structures, to infrastructure gaps, to burdensome regulations.

Successful models often rely on payer-provider partnerships and leverage system-level capabilities.

By changing reimbursement, providers and payers can redefine what services are considered valuable, supporting reductions in unnecessary utilization and improvements in care coordination.

However, payers and providers face barriers to coordination.

Providers may operate in incompatible payment environments, simultaneously trying to fulfill the requirements of both fee-for-service and value-based contracts, where financial incentives (payment for service volume vs. payment for “value”), expectations (e.g., financial risk), and capabilities (e.g., data sharing) differ depending on the type of contract.

Providers must reduce expenditures while still retaining the fixed costs of legacy infrastructure, which remains fragmented by specialty rather than integrated according to patient needs and evidence-based clinical guidelines.

Nevertheless, the experience of successful payer-provider partnerships reveals a basic truth about health care innovation: while good intentions can spark change, strong incentives enable change to last.

Providers must reduce expenditures while still retaining the fixed costs of legacy infrastructure, which remains fragmented by specialty rather than integrated according to patient needs and evidence-based clinical guidelines.

As the public sector bears an increasing proportion of costs, policy makers and health system leaders have sought to identify financing arrangements and care delivery strategies capable of reducing costs and improving population health.

Nevertheless, the experience of successful payer-provider partnerships reveals a basic truth about health care innovation: while good intentions can spark change, strong incentives enable change to last.

Global Case Studies

The Cleveland Clinic is a globally integrated academic health system dedicated to “caring for life, researching for health, and educating those who serve.”

Cleveland Clinic is a 6,690-bed health care system with 22 hospitals and 226 outpatient locations.

The system is comprised of

- 15 hospitals in northeast Ohio, including the 1,294-bed main campus;

- five hospitals in southeast Florida totaling more than 1,000 beds;

- a center for brain health in Las Vegas;

- two outpatient facilities in Toronto;4

- 394-bed hospital in Abu Dhabi and outpatient facility in Al Ain, UAE; and

- an outpatient facility and 184-bed hospital in London.

Each new Cleveland Clinic site seeks to align with this mission, from partnering with payers and policy makers to meet the unique needs of each population, to advancing innovation for the most complex diseases, to recruiting and nurturing local talent for the future.

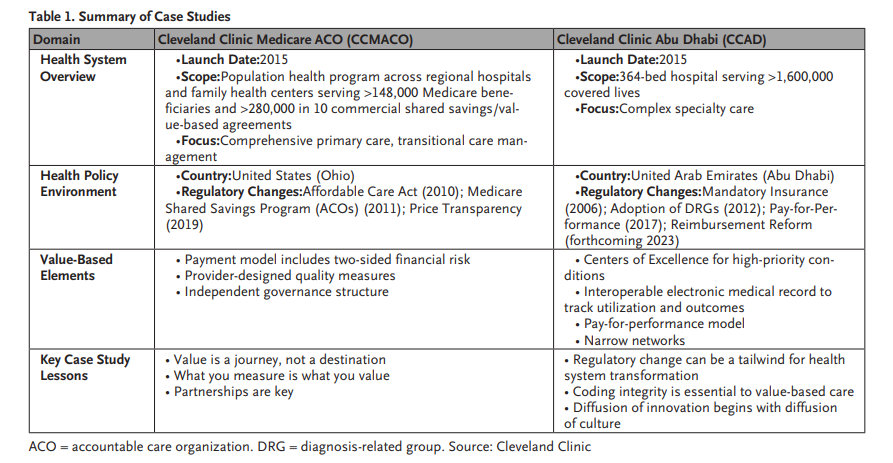

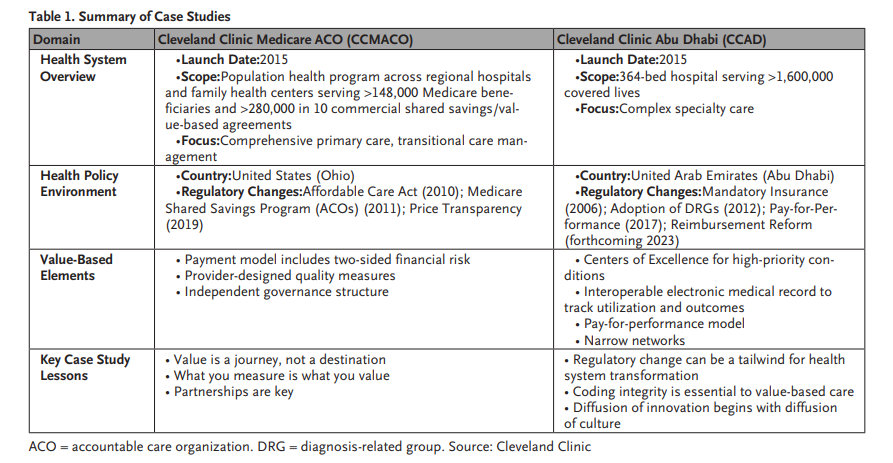

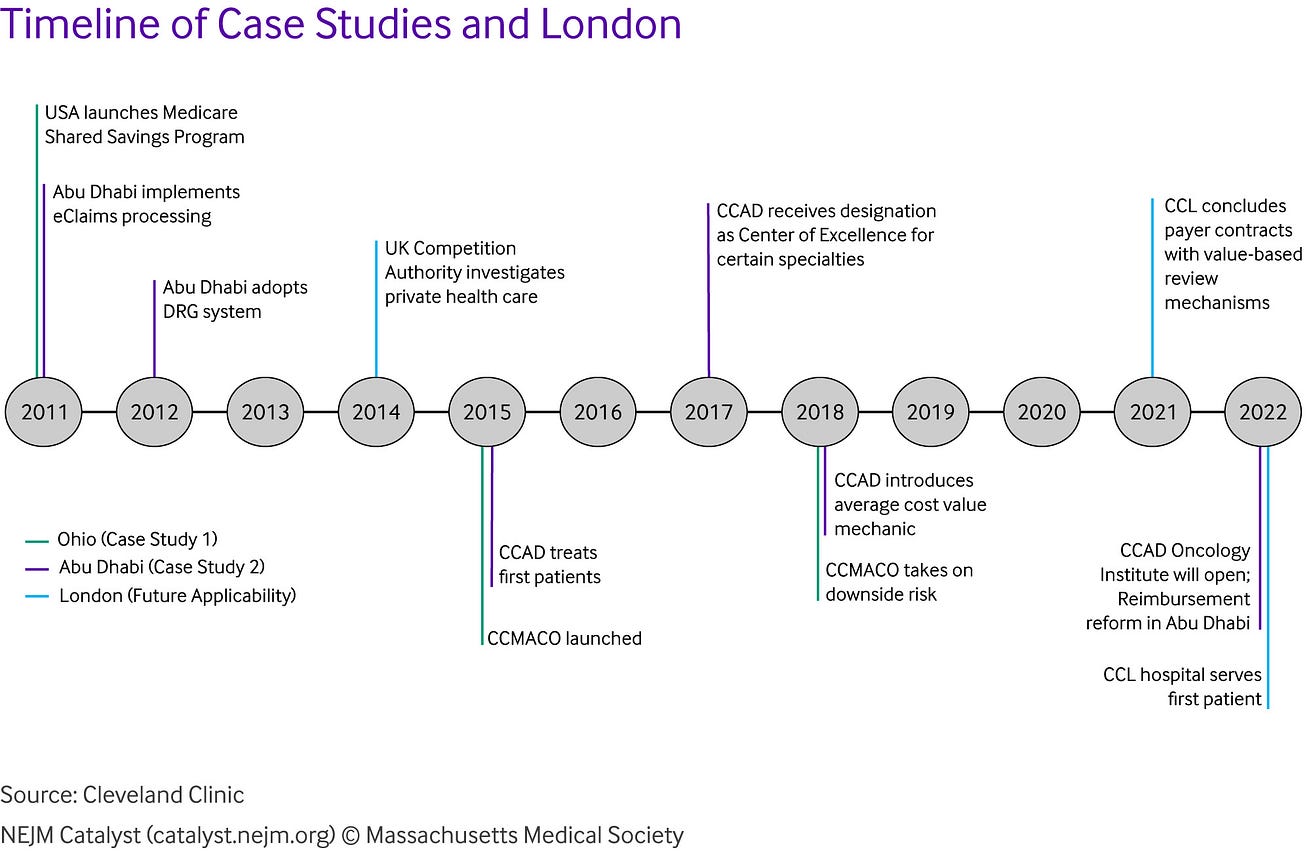

Orienting each system around this mission has enabled Cleveland Clinic to advance value-based care around the world. In this section, we present case studies for how Cleveland Clinic established a value-based model in the U.S. and successfully translated it to the UAE. We also share early learnings for adoption in the UK ( Table 1 and ).

Case Study 1: Cleveland Clinic Medicare Accountable Care Organization (U.S.)

Model Overview

Cleveland Clinic’s Medicare Accountable Care Organization (CCMACO) covers more than 148,000 beneficiaries in northeast Ohio.

Participating provider organizations include Cleveland Clinic’s main campus and regional hospitals, the Cleveland Clinic group practice, and independent primary care physicians affiliated with the Cleveland Clinic Quality Alliance.

Multidisciplinary care teams form the core of CCAMCO’s outpatient chronic disease management program, with these providers connected by investments in information technology (IT) and collaborative governance between patients, providers, and payers.

Evidence is lacking on how to design, implement, and sustain payer-provider partnerships in international markets, including infrastructure investments, operational changes, and contractual best practices.

Policy and Market Context

CCMACO Timeline

Cleveland Clinic joined MSSP in 2015. Because patient attribution for the ACO program occurs at the primary care physician level, Cleveland Clinic formed a separate legal entity to foster partnerships with independent primary care providers in Ohio.

The resulting entity, Cleveland Clinic Medicare ACO, LLC, also established governance structures designed to reflect CCMACO’s commitment to continuous improvement.

For example, the governing body includes a Medicare beneficiary to incorporate an active patient voice during decision-making.

Both independent and employed physicians serve as representatives on the Quality Committee and Financial Committee.

Operationally, CCMACO has developed a team-based model comprising primary care coordinators, population health medical assistants, transitional care management hub caregivers, pharmacists, and social workers.

This multidisciplinary approach, informed by the “team of teams” culture of Cleveland Clinic’s institute model, focuses on managing care transitions to reduce unnecessary utilization.

CCMACO initially only assumed upside risk under MSSP’s Track 1.

The program showed promise from the outset, achieving $42.2 million in savings (of which Cleveland Clinic kept 3%) and a quality score of 96.3% by 2016.

This foundation for value prepared Cleveland Clinic to transition to downside risk, entering Track 1+ in 2018.

Under this program, ACOs become eligible for shared savings up to 50% in exchange for a fixed loss sharing rate of 30%.

By 2020, the final quality score exceeded 98.1% with $9.56 million in savings.

Of this sum, 75% was distributed to ACO participants, 15% was invested in infrastructure, and 10% was invested in redesigned care processes and resources.

Lessons from CCMACO later informed the dissemination of value-based care principles to Cleveland Clinic Florida, which established its own ACO model in 2018 that currently encompasses nearly 36,000 beneficiaries in a one-sided risk model.

Cleveland Clinic Florida maintains select contracts with limited downside risk (AvMed and Florida Blue), and it will expand its ACO to downside risk once it further enhances its operating model and capabilities.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

- 1.Value is a journey, not a destination

- 2.What you measure is what you value

- 3.Partnerships are key.

1.Value is a journey, not a destination.

Cleveland Clinic already had many of the ingredients of value-based care: physician salaried employment model, integrated financial management platform, interoperable electronic medical records, culture of improvement, and ethos of innovation.

However, piecing together new payment and delivery models requires thoughtful planning and collaboration, and a willingness to challenge norms for how care is governed and delivered.

To this end, CCMACO convened different stakeholders to develop the governance models, legal arrangements, and care teams that would assume accountability for the ACO population.

CCMACO’s leadership also developed a phased approach for titrating financial risk from Track 1 to Track 1+, therefore transitioning from upside risk only to both upside and downside risk, to provide sufficient space for the model to achieve “wins” (that is, demonstrate shared savings) and make adjustments (e.g., new partnerships).

2.What you measure is what you value.

Well-designed performance measures provide valuable insight to providers and system leaders about areas for improvement and investment.

However, measures must be rooted in outcomes that matter to patients. Metric development should be a collaborative process accounting for both physician and patient perspectives.

CCMACO incorporated this principle into its contracting mechanism, creating a formal Quality Committee within the ACO legal entity that included both employed and independent physicians.

This cocreation process fostered accountability, while investment in enterprise analytics created mechanisms to track and measure performance.

To supplement the primarily process-based ACO quality measures, CCMACO invested in quantifying the patient experience through the use of rigorously designed patient surveys, the creation of an advanced patient registry, and focusing on patient experience through leadership rounding and continuous improvement projects led by a physician Chief Experience Officer.

Piecing together new payment and delivery models requires thoughtful planning and collaboration, and a willingness to challenge norms for how care is governed and delivered.

3.Partnerships are key.

Value is achieved, or lost, at the margins of care delivery: hospitalizations, procedures, discharges, follow-ups, and care transitions.

Team-based models and partnerships help to close gaps in the care continuum.

For example, CCMACO created a Transitional Care Management Hub, where caregivers focus on preventing readmissions by coordinating patient handoffs back to their primary care provider and collaborating with pharmacists to provide services such as medication reconciliation.

CCMACO also partnered with other care delivery organizations in the region.

We included independent primary care practices in the Cleveland Clinic Quality Alliance, and partnered with high-quality skilled nursing facilities to reduce length of inpatient stays.

We included independent primary care practices in the Cleveland Clinic Quality Alliance, and partnered with high-quality skilled nursing facilities to reduce length of inpatient stays.

Case Study #2: Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi

Model Overview

Cleveland Clinic expanded its international footprint in 2015 by opening a hospital in the UAE.

In contrast to CCMACO’s primary care focus, Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi (CCAD) focused on introducing technological and clinical innovations for specialties such as cardiac, transplant, and neurological care.

CCAD also leveraged the new “institute” model of Cleveland Clinic, with care organized around multidisciplinary teams for diseases and organs rather than traditional academic departments.

To expand coverage for new treatments and service lines and support payment system modernization, CCAD collaborated closely with the Departments of Health and Finance, and public and private insurers.

As of December 2021, CCAD has completed over 3.2 million outpatient visits, 94,000 surgeries and served 312,000 unique patients from over 80 countries.

Policy and Market Context

CCAD’s creation occurred amidst significant health system reform in the UAE, including the development of mandatory health care coverage and the adoption of prospective payment methodologies.

The Emirati population has faced a growing disease burden exacerbated by gaps in specialty care, particularly for complex procedures, resulting in increased costs for both payers and the Department of Health.

Together, the competitive market, evolving policy landscape, and opportunity to reduce pressure on public budgets and improve population health outcomes presented a unique environment for value-based care.

CCAD Timeline

CCAD is a joint venture between Cleveland Clinic and Mubadala Investment Company that employs physicians from more than 55 sub-specializations in its 14 institutes (including 6 centers of excellence).

In addition to expanding specialty care capacity, CCAD also introduced innovations across many diseases.

For example, CCAD became the market leader for services in cardiology (e.g., transcatheter aortic valve replacement) and digestive disease (e.g., robotic-assisted subtotal pancreatectomy).

CCAD has demonstrated great ability to provide high-quality care for patients with severe illness and conditions, treating a patient population with a case mix index (CMI) of 3.73 by the end of 2021. (CMI represents a relative value assigned to a diagnosis-related group of patients in an inpatient setting.

It is used in determining the resources required to provide care, and thus gives an indication of level of acuity.

By comparison for year-end 2021, the CMI for Cleveland Clinic was 1.94, with the Medicare CMI for Main Campus being 3.02.)

Contracts with the government and key private insurers helped establish CCAD’s base population, which by 2019 exceeded more than 1,000,000 covered lives, the majority of whom were Emirati nationals.

Likewise, the shift from inpatient to outpatient cases required engagement regarding Abu Dhabi’s payment methodology, which reimburses same-day procedures through per diem charges, inpatient encounters through international refined diagnostics-related group (IR-DRG) payments, and outpatient visits through fee-for-service.

For instance, service code specifications required patients to be admitted for more than 12 hours to account for markedly higher DRG reimbursement given that per diems did not allow hospital additional reimbursement for pathology, secondary procedures, consumables, and prostheses.

Under this system, potential financial misalignments could discourage clinical innovations that could offer benefits for safety, effectiveness, and convenience.

Metric development should be a collaborative process accounting for both physician and patient perspectives.

Additional reimbursement reforms are ongoing, and CCAD continues to prominently partner with the government to advocate sustainable solutions using the hospital’s 7 years of data reflecting tertiary-quaternary care delivery (e.g., extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO] and transplants).

Through July 2022, the Abu Dhabi Department of Health continues to use feedback from providers and payers to iterate its reimbursement system, including: changes to episode definitions; DRG pricing and weights; and adjustment mechanisms, both for quality-based institutional metrics and for outlier cases.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

- 1.Enabling regulations and strategies at the health-system level is essential for value-based care.

- 2.Coding integrity is essential to value-based care.

- 3. Diffusion of innovation begins with diffusion of culture.

1.Enabling regulations and strategies at the health-system level is essential for value-based care.

Abu Dhabi’s health care reforms were instrumental in incentivizing new care delivery models.

While the regulatory environment continues to evolve, Abu Dhabi pushes for improved performance and collaboration between payers, providers, and policy makers.

CCAD capitalized on this emphasis to navigate new terrain and improve access and outcomes.

CCAD’s experience illustrates how genuine payer-provider partnerships are necessary to modernize coverage policies and expand service offerings according to population needs.

For example, CCAD has engaged payers and regulators on Abu Dhabi’s new JAWDA program (Arabic for “quality”), which contains guidelines covering 19 services including pivotal offerings such as one-day procedures, cardiac surgery, and stroke.

2.Coding integrity is essential to value-based care.

Value does not exist in a vacuum; the unique needs of patients determine definitions.

Consequently, payment systems must be calibrated to account for differences in individual care needs and the population’s disease burden to ensure appropriate resource allocation.

CCAD has the UAE’s highest case-mix and has introduced novel procedures and technologies to advance specialty care.

Partnerships with payers and ongoing dialogue with regulators have enabled meaningful progress in coding and claims processing, including coverage for germline/somatic testing for oncotype diagnosis of breast cancer and pharmacotherapy consultations for heart failure and post-transplant patients. CCAD’s experience illustrates how sustainable financing for clinical innovation requires aligning incentives across contracting and coverage policies to support a checks-and-balances approach to billing.

Regular engagement among CCAD, payers, and regulators has also allowed better measurement of episodic costs through appropriate coding alignment.

3. Diffusion of innovation begins with diffusion of culture.

While delivery models are portable, the “secret sauce” of culture and continuous improvement can prove challenging to replicate.

CCAD leveraged enterprise capabilities to translate the Cleveland Clinic’s three-pronged culture of patient care, scientific research, and clinical education to the UAE.

First, CCAD adopted the same employment (salaried physicians) and organizational model (clinical institutes).

Second, CCAD used the same electronic medical record as Cleveland Clinic’s main campus, enabling replication (with localization) of care processes.

Third, many members from various levels of organizational hierarchy at CCAD came directly from Cleveland Clinic, providing continuity in leadership and vision.

Seeding the new system with U.S. leaders helped instill the Cleveland Clinic culture of “patients first” at CCAD and support the system’s integration into the global Cleveland Clinic enterprise.

Importantly, CCAD also recruited health care leaders from the UAE to its leadership team and hired hundreds of Emirati nationals from both the local community and abroad. Lastly, CCAD also invested in graduate medical education in the UAE to develop a pipeline for future talent.

Future Applicability for Cleveland Clinic London

As CCL has only recently started serving patients, data-informed lessons learned would be premature, although CCL started regularly engaging payer and regulatory partners 5 years prior to launching clinical operations.

We identify two takeaways from this process:

First, given the long lead time on IT system enhancements and the complicated multi- and interdisciplinary nature of integrated care pathways, CCL initiated internal designs of care paths across IT, clinical institutes, allied health professions, safety and quality, and finance teams in 2018.

CCL started sharing symptom-based pathways with payers in 2019 to secure stakeholder partnership and collaboration.

Abu Dhabi pushes for improved performance and collaboration between payers, providers, and policy makers.

CCAD capitalized on this emphasis to navigate new terrain and improve access and outcomes.

Second, new market entrants do not have their own historical data to use for benchmark comparison.

While value-based care is nascent in the UK, CCL is leveraging enterprise analytics and codifying data exchanges and collaboration with payers from past experiences in the U.S. and the UAE to demonstrate de novo the potential cost savings from a new value-based model.

CCL has incorporated value-based review mechanisms into its payer contracts, creating legal and operational structures to codevelop measures, exchange and review performance data to drive systematic improvements, and execute charge adjustments accordingly based on theoretical projections stemming from payers’ historical utilization and agreed pricing with CCL.

Discussion

Health care as an industry has at least a theoretical commitment to continuous improvement.

However, one must distinguish between activities that are value- added and models that are value- based, with value previously defined as outcomes per dollar spent.

As illustrated in Figure 2, value-based care models must be patient-centered, with cost, quality, and outcomes mediated by the relationship between providers and payers.

Each entity contributes respective enablers for value.

A provider’s culture and governance, care model and pathways, costing capabilities, and digital and technology functions represent enablers on the delivery side, whereas the payer’s population profile, financial model, evaluation capabilities, and digital and technology functions function as the enablers on the payment side.

These interactions are further influenced by the policy and market environment in the provider’s location.

These case studies illustrate how carefully designed and well-executed payer-provider partnerships help deliver value-based care in different clinical and cultural contexts.

Table 2 summarizes examples from the case studies for each of the enablers of value-based care models presented in .

For example, the care pathways model for CCAD represents a unique enabler for value-based delivery in the Abu Dhabi market.

Likewise, the CCMACO value-based steering committee provided an organizational culture and governance of empowering physicians to serve as leaders and cocreate the quality measures for which they would later be held accountable.

On the payment side, the evaluation capabilities of the Department of Health in Abu Dhabi enabled the transition to prospective payment and pay-for-performance.

The profile of the insured population also frames the orientation of care delivery.

For instance, because most Medicare patients are age 65+ and often have multiple chronic diseases, payers needed to calibrate financial incentives and quality measures around improving disease management.

CCMACO’s emphasis on primary care and population health impacted this important aspect of the patient journey.

Collaborations among regulators, providers, and payers were critical for navigating local policy and market environments.

For example, CCAD had to work with regulators on updating coding and coverage policies for novel technologies to address tertiary-quaternary care gaps that previously resulted in longer episodic costs or Emiratis receiving more expensive treatment outside of their home country.

As the value-based care framework in and the examples in Table 2 demonstrate, strategic planning, early investment in governance models (including steering committees and clinical institutes), and a long-term commitment among all parties can propagate care models to achieve the shared goals of better outcomes at a lower cost — even in environments new to value-based care and payer-provider partnerships.

To illustrate the generalizability of Cleveland Clinic’s experiences designing, building, and sustaining value-based care models, we offer the following four cross-cutting lessons.

- 1.Proactively Plan to Streamline Implementation

- 2.Establish a Governance Model for Value-Based Care

- 3.Develop Infrastructure and Frameworks for Data-Driven Decision-Making

- 4.Focus on the Whole Patient Journey

1.Proactively Plan to Streamline Implementation

Engaging with policy makers to help streamline regulations is critical to guide hospital networks’ approach to new geographies.

For example, in the UK, a Competition and Markets Authority investigation illustrated the need for new entrants, while in the UAE, a focus on reducing the need for UAE nationals and residents to travel overseas to receive complex treatment preceded a drive to operate under prospective environments and introduce tertiary-quaternary care provisions.

Value-based care models must be patient-centered, with cost, quality, and outcomes mediated by the relationship between providers and payers.

2.Establish a Governance Model for Value-Based Care

For value-based models to succeed, providers must clearly define and refine responsibilities, governance models, and terms of engagement when contracting with payers.

The case studies illustrate the importance of inclusive and empowered governance models to foster accountability and drive decision-making.

For example, CCMACO developed a formal legal entity for the ACO that included representation from independent providers who had entered into a partnership with Cleveland Clinic, enabling providers to support designing the performance measures for which they would ultimately be accountable.

Likewise, CCL from the outset has included committee structures in its contracts with payers with details proposing representation, developing meeting structures, and identifying action items.

3.Develop Infrastructure and Frameworks for Data-Driven Decision-Making

Infrastructure for data collection and exchange requires proactive development.

For example, Cleveland Clinic has used the same electronic medical record platform at each of its care sites, creating global connectivity.

Likewise, developing the capacity to share data across platforms and review progress at regular intervals will strengthen the partnership between payers and providers.

Providers may possess key data on clinical metrics (e.g., hospital-acquired infections), while payers may possess key data on utilization metrics (e.g., referral experience for patients).

From an implementation perspective, data sharing may pose complications, and may require navigating regulations on patient privacy (e.g., HIPAA in the U.S., the EU General Data Protection Regulation, and the UK’s own adoption of GDPR and Data Protection Act, as may be further amended post-Brexit).

Solving for these challenges from the outset prevents future roadblocks.

Lastly, not all data is made equal: measurements should be relevant, timely, informative, and actionable.

Providers and payers should create dashboards with KPIs from agreed sources of truth to measure progress and guide decision-making.

4.Focus on the Whole Patient Journey

Interest in value-based care will continue to grow as health care reforms accelerate around the world.

While payment and delivery reforms are the primary focus of value-based care, it is necessary to acknowledge the important roles of suppliers, drug and device makers, and IT developers, all of which are beyond the scope of this article.

Nevertheless, the global case studies in this article offer lessons for health care leaders from our efforts to design, implement, and sustain partnerships in different international markets.

Although the nuances of challenges and solutions for health care innovation will differ, the overarching goal should remain the same: deliver value as defined and measured ultimately with the patient at the center.

About the authors and affiliations:

Chibueze Okey Agba, MBA

Chief Financial Officer, Hartford HealthCare, Hartford, Connecticut, USA

Joshua Daniel Snowden-Bahr, JD, MHA

Regional Director, Contracting & Business Development (International Markets), Market & Network Services, Cleveland Clinic Health System, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Kushal T. Kadakia, MSc

MD Candidate, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Samer Abi Chaker, MD, MPH

Health Care Program Leader, CAPADEV LLP, Dubai, UAE

James B. Young, MD

Executive Director of Academic Affairs, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA; Professor of Medicine & Vice Dean for Academic Affairs, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Alex G. Forystek

International Payer Contracts Manager, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

References and additional information

See original publication

Originally published at https://catalyst.nejm.org on June 28, 2022.