Both financial and nonfinancial benefits depend on employees working with and trusting AI.

Linkedin

Sam Ransbotham

Professor at Boston College;

AI Editor at MIT Sloan Management Review;

Host of “Me, Myself, and AI” podcast

December 7, 2021

AI ethics are easy to espouse but hard to do. How do we move from education and theory into practice?

You rarely (never?) hear someone publically advocate for ethical shortcuts or deceptive practices. With AI and ML, I suspect that most ethical problems are not due to diabolical intent but are instead unintentional. They may stem from a loss of perspective that comes with datasets with many many rows. But a row that is just another row in a giant dataset to one person is critically important to the person that row represents — it is that person’s job application, loan, grade, court case, etc. The current scale of AI and ML data can exacerbate the difficulties organizations have in ensuring ethical processes.

With ethics, technology can be a force for good.

In last week’s episode of the “Me, Myself, and AI” podcast, Shervin and I talked with Paula Goldman, Salesforce’s first chief ethics and humane use officer, about how the CRM provider considers risk and fair outcomes in its product design. Paula pointed out how human decision-making is certainly subject to bias. But now, with AI, we have the potential to improve that bias by incorporating human judgment and appropriate guardrails. We’ve spoken with AI ethicists before, though it was refreshing to hear from Paula, who develops and implements responsible tech policies inside a customer-facing organization.

Salesforce offers specific examples of tech initiatives by building with responsibility and transparency in mind. Many other organizations are considering internal policies. For example, the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit’s recently established responsible AI principles. UNICEF’s Global Insight and Policy team produced a series of case studies on responsible tech, specifically related to children. We’re seeing progress.

Inside organizations, realizing these ethical benefits with AI requires trust.

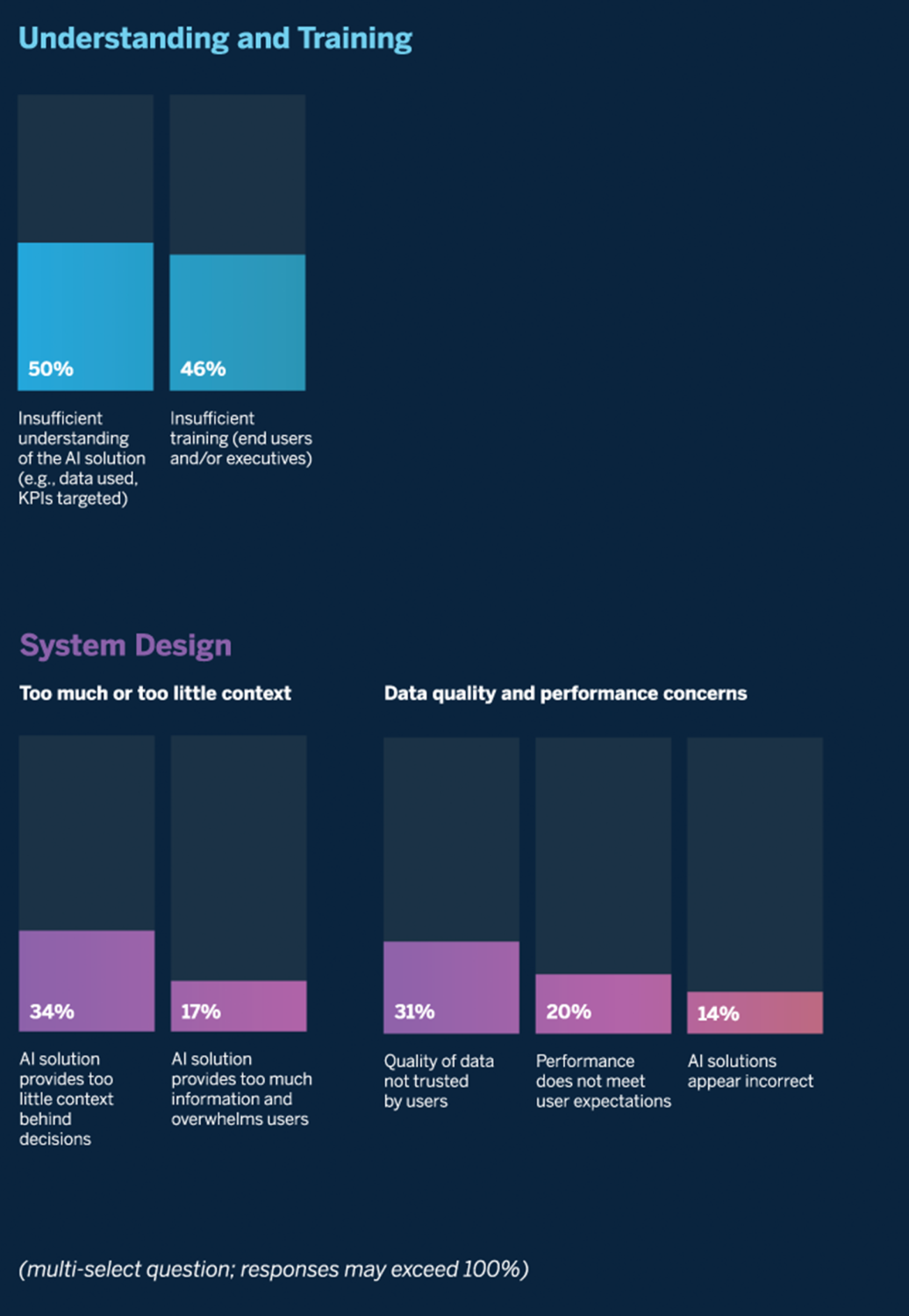

Our recent research on the cultural benefits with AI finds that both financial and nonfinancial benefits depend on employees working with and trusting AI. Unfortunately, end users may mistrust AI solutions for many reasons.

For example, many respondents believed that mistrust of AI stemmed from a lack of understanding (49%) or training (46%). Our report describes an example from Paul Pallath, global technology head of data, analytics, and AI at Levi Strauss & Co. The company believes that understanding is critical and has invested significantly. For example, it selected employees “from various different domains, from the retail store to people in IT to people in business, and called them into an eight-week, highly immersive AI/ML boot camp.” Our report describes how Pallath believes the investment was worth it because “they need to have trust. And building trust in AI/ML and machines can only happen if people themselves are part of the process rather than being subjected to it.” See our report for additional reasons that people mistrust AI.

Improving ethical practices may require different objectives and new oversight.

The ubiquity of algorithms in daily life raises questions about ethics, transparency, and who’s monitoring how those algorithms work. Mark Nitzberg, executive director of the UC Berkeley Center for Human-Compatible AI, recently explored a user-centric approach to algorithm design in MIT Sloan Management Review, noting that “The biggest concerns over AI today are not about dystopian visions of robot overlords controlling humanity. Instead, they’re about machines turbocharging bad human behavior.” Technology once again indiscriminately amplifies.

“The biggest concerns over AI today are not about dystopian visions of robot overlords controlling humanity. Instead, they’re about machines turbocharging bad human behavior.”

One analogy I’ve made is to the food industry and the changes that flowed from the publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle in 1906: “We have disturbingly little idea how many of the algorithms that affect our lives actually work. We consume their output, knowing little about the ingredients and recipe.” I see many analogies to the way we currently consume data. In the food industry, it took regulation, and we’re seeing that with technology, such as in the EU’s approach to regulation or NYC’s law that requires audit of algorithms used in hiring.

From my article on transparency in the food industry: “With more transparency into the algorithms in use, we can have informed discussions about what may or may not be fair. We can collectively improve them. We can avoid the ones we are allergic to and patronize the businesses that are transparent about what their algorithms do and how they work. A side effect of the insight into food processes was the collapse of the market for lemons; consumers wouldn’t purchase suspect ingredients or elixirs with dubious claims. Similarly, we’ll likely find that some businesses are covered-wagon sideshows selling snake oil, and we can knowledgeably avoid the results of their unfair or sneaky algorithms.”

Thanks for reading, and let me know your thoughts.

Join AI for Leaders, an exclusive group on LinkedIn, curated by the creators and hosts of Me, Myself, and AI, for more resources and conversation.

Subscribe to Me, Myself, and AI anywhere you consume podcasts.

Originally published at https://www.linkedin.com.